The Mythic Role of Space Fiction

by Sylvia Engdahl

This essay is based on my Phoenix Award acceptance speech presented at the Children's Literature Association Conference, San Diego, June 1, 1990. Slightly different versions published in Journal of Social and Biological Structures, Vol. 13, pp. 289-295 (1990). Copyright 1990 by JAI, Inc.; Work and Play in Children's Literature, Susan R. Gannon and Ruth Anne Thompson, eds., Children's Literature Association, 1991; and The Phoenix Award of the Children's Literature Association 1990-1994, Alethea Helbig and Agnes Perkins, eds., Scarecrow Press, 1996.*

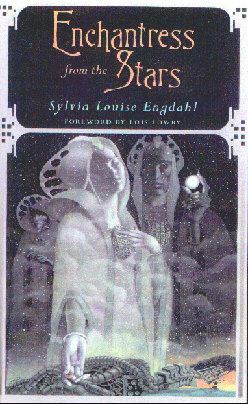

It's always encouraging for an author to find that readers like a book, but especially so to discover that they still like it after the passage of many years--particularly when it has been out of print for a long time, as mine was until shortly before receiving the Phoenix Award [and again more recently]. In my case, I had thought my days as a writer of fiction were long behind me, for the period of my life during which I had ideas for fiction was a relatively short one. Learning that I had been chosen for the award [which is given annually by the Children's Literature Association for the best book published 20 years earlier] happened to coincide with major changes in my personal life, and it seemed a fitting symbol for the sense of renewal I had never expected to experience.

I was especially happy to know that Enchantress from the Stars appeals to today's audiences, because that fact is evidence for views I've long held about the cultural significance of space fiction. I have been developing these views in nonfiction, beginning with a course I taught by computer conferencing through Connected Education, an organization that offered graduate courses, open to students in all cities, for credit from New York's New School for Social Research. My course [now online] dealt with the relationship between science fiction and myth. I feel popular-culture science fiction should been seen as an emerging body of mythology for the Space Age, and that's the topic about which I'd like to speak here.

It's a difficult subject to approach because the terminology involved is so ambiguous. It usually took at least a week of discussion with my students to make clear the context in which I use the terms "myth" and "science fiction," so bear with me if I don't wholly succeed in doing it in this short summary. The first crucial thing to emphasize is that I am not talking about science fiction as a literary genre. Though people in the children's literature field usually describe me as a science fiction author, that's not quite accurate according to how people in the science fiction field look at it. In terms of publishing and reviewing categories my books weren't initially issued in that field, and while some of them--especially the Children of the Star trilogy--are enjoyed by adult SF fans, I have always tried to make them intelligible to a general audience rather than just to readers with science fiction background. This, rather than the fact that they were originally published for young people, means that most of them, Enchantress from the Stars in particular, don't fit the category of genre-oriented SF. Similarly, other expressions of Space Age mythology do not, for they also involve concepts already embedded in the public consciousness.

To many science fiction specialists, literary quality lies in the use of new and original concepts that haven't been seen before. I was once advised that to write for the SF market I'd need to slant my books toward people who had read at least 500 science fiction novels previously--and that was over 25 years ago. Nowadays, to appeal the hard-core science fiction fans, ideas must be much farther out than that. There's nothing wrong with this goal, but it doesn't happen to be my goal. What I try to do is to use images and metaphors that are familiar and meaningful to everyone in our Space Age culture. One reason I wrote for young people in the first place was that it was, at that time, the only field in which a serious author was permitted to do so.

There is one other area in which these metaphors are used, however, and that's in filmmaking. Films, unlike books, are designed for wide audiences rather than specialized ones. Therefore, in my course about Space Age mythology, we discussed films more than written literature; only a few classic science fiction novels qualify as as expressions of our culture's widespread, popular mythology. Most space films are scorned by fans of the literary science fiction genre, who don't consider them "real" science fiction; George Lucas himself called his Star Wars trilogy "space fantasy" because he knew that. But the general public regards these films as "science fiction." So we can't get away from the term, much as I feel we need a distinct one. I was even forced to include it in my course title, since there's no adequate substitute for it in combination with the words "Space Age"--but I carefully omitted it from the title of my speech.

It's worth noting that the earliest major hits among space films, Star Wars and E.T. for example, were considered children's films although they attracted very large adult audiences. In the seventies when I was writing my novels, young people had more of a Space Age outlook than most adults did. That's changing, I think, because the children and teenagers of that era have grown up, and they haven't lost the view of the universe they started out with.

But it's also quite possible that the mythological aspect of space fiction once caused it to be branded as "kid stuff" for the same reason that traditional myths and fairy stories were considered mere children's stories, despite having been meaningful to adults in the cultures that developed them. This too is changing, because interest in the study of myth has greatly increased during the past decade. It has been brought to the attention of the general public, for example by the Joseph Campbell television series, which led to the popularity of his earlier classic work in the field. That, incidentally, was a direct consequence of the impact of Star Wars, in two ways, I think. First, Star Wars was influenced by Campbell's theories, as George Lucas took pains to acknowledge; the Campbell TV series was filmed at his Skywalker Ranch. But even more significant was the fact that Star Wars and other widely-seen space films embodied the emerging mythology of our own era, a body of myth in which not only the timeless underlying ideas, but the imagery and metaphors, speak to Space Age generations.

And that made people realize, if only unconsciously, that myth is not something left over from the childhood of our civilization, now useful only for the entertainment of children. It is a living, vital force that reflects the beliefs, questions and aspirations of the culture from which it arises. This is true, I believe, in a wider sense than the now-popular sense in which myth is viewed as having psychological validity; and it's these other aspects of myth on which my own study is focused.

Because of the new awareness engendered by the work of Campbell and others, I don't need to elaborate as I once would have on the fact that I'm not using the term "myth" in the sense of a synonym for "falsehood." I'm speaking of metaphors, not lies or mistaken beliefs. I must make plain, however, that in referring to space fiction as myth, I do not mean to suggest that any particular author or filmmaker has created a myth, or that a single film or book--least of all my own--in itself constitutes a coherent new mythology. Nor do I mean that science fiction authors have deliberately drawn on traditional myths for themes, although some may indeed do so and identification of these elements is a valid aspect of literary analysis.

To those familiar with the study of literature, these points can be quite confusing. My seminar was a Media Studies course, not one on literature or writing, but students didn't always see the difference in emphasis. They tended to suppose that a new mythology should be based on conscious, skillful use of concepts derived from old mythologies, and that the artistic quality of the new should be higher than that of traditional stories in their original, unpolished form. But that's not the sort of mythology I'm talking about. I'm referring not to purposeful creations, but to the common body of concepts and images on which popularly-accepted space stories now draw.

Here we come to another likely area of misunderstanding, because most mythologists, even--or perhaps especially--today, would say that the only underlying concepts involved are eternal psychological truths that do not change from one body of mythology to another. Followers of Jung, for example, would say that mythological archetypes are a constant. I certainly don't dispute this, because I do believe in the existence of such universal truths, even though I don't wholly agree with any existing theory about what they are. However, I maintain that such truths are not the only element in a mythology. If they were, why would particular mythologies be more meaningful in some cultures than in others? And why would traditional mythologies be losing their power in contemporary culture, as is generally acknowledged to be the case? These are questions to which no psychological theory of myth provides an adequate answer. There is, I think, far more to myth than significance in terms of the psyche, however great that may be.

The usual explanation for traditional mythologies having lost their power, and one about which Campbell wrote a great deal, is that their imagery is based on a pre-Copernican universe and is not relevant to the world we now know. Certainly this is true, though some fail to recognize it. The noted psychologist Bettleheim (whose work George Lucas also acknowledged as a source of themes) wrote in 1976, "To tell a child that the earth floats in space, attracted by gravity into circling around the sun, but that the earth doesn't fall into the sun as the child falls to the ground, seems very confusing to him. The child knows from his experience that everything has to rest on something, or be held up by something. Only an explanation based on that knowledge can make him feel he understands better about the earth in space. More important, to feel secure on earth, the child needs to believe that this world is held firmly in place. Therefore he finds a better explanation in a myth that tells him that the earth rests on a turtle, or is held up by a giant.... Life on a small planet surrounded by limitless space seems awfully lonely and cold to a child--just the opposite of what he knows life ought to be." (The Uses of Enchantment, Vintage Books, 1977, p. 48.)

Well, one wonders just who is confused and lonely here; one is in fact reminded of Pascal's well-known comment about the terrifying eternal silence of the infinite spaces! The child of today is more apt to see planets in space as natural, beautiful, and perhaps exciting. But it's no longer necessary to debate about issues like this; we have only to count the children (if any) who prefer myths about the world being held up by turtles or giants to the mythological imagery of Star Trek.

But I have not been quite fair to Bettleheim with these remarks; in reality he was arguing not for a specific myth, but for the value of mythological explanations to children too young to grasp scientific ones. He took it for granted that any description of the earth in space was "scientific"; he was unware of the emerging Space Age mythology, which even in the mid-seventies, had yet to reach mass audiences. It is quite true that only myth can make the larger environment of our species understandable to most of its members--adults as well as children--and that is precisely the function that space fiction fulfills. Campbell, ironically I think, felt we don't yet have a new mythology and that our culture is seriously lacking in this respect; I believe that we have a developing one, as appropriate to our era as those of earlier cultures were in the eras from which they arose.

Among anthropological theories of myth, the one that strikes me as soundest holds that mythology deals with human relationship to environment. It is an adaptive feature of a culture, in the sense that all cultural phenomena, like biological ones, serve adaptive purposes; it's a way of confronting the environment in which the members of the culture perceive themselves to be living. Melville and Frances Herskovits (Dahomean Narrative, Northwestern University Press, 1958, p. 81) wrote, "As a point of departure, we may define a myth as a narrative which gives symbolic expresssion to a system of relationships between man and the universe in which he finds himself." And if mythology is a symbolic expression of relationships between human beings and their environment, then of course, if the environment changes in a fundamental way, the mythology must change. I believe that the Space Age mythology is an instinctive response to the first major change in human environment since prehistoric times.

The natural environments of particular cultures at particular stages of their histories have differed extensively in details, but all have had certain things in common. All have encompassed one earth, however differently its dimensions may have been conceived, and one inaccessible sky containing one sun, one moon, and stars unreachable by mortals. It is no wonder that perception of an environment encompassing many accessible worlds, even many suns, with dark space in between, is a change of sufficient magnitude to evoke a culture-wide mythology with impact unprecedented in the modern age.

To be sure, not everybody agrees that expanding to other worlds is feasible or even desirable, but that is somewhat beside the point. Vast numbers of people in our culture now think in terms of an interplanetary, rather than merely planetary, environment for the species homo sapiens, even if they see no practical means of using the whole environment. It's there. Among young people in particular, it is assimilated as an unquestionable fact of nature. This can be declared a mistaken worldview, but it cannot be dismissed as nonexistent, any more than the worldview of any other culture can be so dismissed. And worldview is not an aspect of mythology; it is primary, while the mythology to which it gives rise deals symbolically with ideas about its features. There have been analysts of space myths who've tried to write them off as escapism, assuming they must be based on some unhealthy subconcious motivation; but this is to ignore the undeniable existence of the worldview on which they are founded.

One can look at this two ways: one can observe that the worldview does exist, and see how the new mythology is emerging from it, or, if one is unsure how our culture now views the universe, one can observe the popularity of space fiction and interpret it as evidence for the interplanetary worldview's prevalence. It seems to me very strong evidence indeed, especially considering the fact that far more people respond to space films than are eager to see funds allocated for space exploration. I would even venture to suggest that a good many adults are unaware of their own worldview on the rational level and are so far confronting it only on the mythopoeic one, else why were Star Wars and E.T. the highest grossing films ever made?

Mythological space fiction portrays our feelings about the universe we live in. Its does not accurately explain the universe, because by definition, myth deals metaphorically with things of which we have no literal understanding. Space stories that deal with something we really know about (for instance, travel to the moon within our era) are not part of our culture's mythology any more; they're simply fiction, no matter what label is put on them. There are no metaphors involved, at least not apart from those concerned with individual psychology. Metaphors are needed only for things where the reality is likely to be quite different from our current conception.

It's important to understand that though established myths may be used for didactic purposes, at the time of their emergence they have no such function. I surely don't mean to imply that the features of Space Age mythology are what form our culture's views--it is the other way around. Although there's certainly a feedback effect, in the sense that young people reading space fiction are influenced by it, a mythology reflects a culture's underlying views; it does not produce them. A culture adopts metaphors for aspects of the already prevalent outlook that it's not ready to deal with in factual terms. And this is in addition to the very real use of metaphors in myths to represent timeless psychological realities.

Starting from these premises, there is a great deal to be said about various aspects of the Space Age worldview and the ways they are reflected in specific books and films. In a two-month seminar we by no means covered the ground, and so I can barely touch the surface here. What I'd like to do is to give you a few brief examples in terms of Enchantress from the Stars. The significance of these lies mainly in the fact that I had no conscious understanding of them at the time I was writing the story in 1968, much less when I first conceived it back in 1957. All this theory has come to me since then, and I have been quite surprised by what I found in my own book.

Some aspects of it were deliberate, of course. Obviously I did write the fairy tale sections in a purposefully mythological form. Not so obviously to some of the reviewers, I also meant the portrayal of the invaders to be recognized as mythic--some called them "stereotyped," which of course they were, but this was comparable to the intentional stereotyping of the fairy tale heroes. Real interstellar explorers aren't going to blast people with comic-book style ray guns any more than real medieval woodcutters attacked dragons with swords, but the mythology of the early Space Age has envisioned them that way.

So what I thought I was writing, and what many readers may still assume I wrote, was a story about two mythic civilizations and one purely fictional civilization--highly oversimplified, to be sure, but nevertheless showing a potentially real future. The extent to which the "realistic" portion of the narrative contains fantastic elements, as opposed to merely imaginary ones, depends on individual opinion concerning the reality of interstellar travel and of controlled psychic powers; personally I take both these possibilities seriously. I naturally don't believe people of other planets look just like us, any more than I believe they speak English; both the physical descriptions and the language were necessary literary devices. But that the very concepts of interplanetary invasions and interstellar federations are metaphors of a newer mythology, no closer to actual fact than the concept of dragon-slaying, was something I didn't recognize until a friend pointed it out to me four years after the book was published.

In actuality, all three viewpoints of the book are equally mythological, equally stylized. I still believe strongly that humankind will expand throughout the universe someday, but it won't happen in any way we can presently envision. Does this invalidate the story if it's taken, as I meant it to be taken, as speculation about the universe rather than allegory about relationships on our own planet? Not at all. I would not write it any differently if I were doing it today. But my not having known what I was doing illustrates the fact that metaphors of a living, growing mythology are absorbed by the writers who make use of them, rather than created. At the time, it never occurred to me to doubt the literal existence of a galactic Federation.

Most contemporary space enthusiasts do believe literally in the Federation, whether or not their guesses about its policies match mine--ask any Star Trek fan, or for that matter, any radio astronomer who supports the SETI project. That's why my story rang true to readers. The fact that in the eyes of the Phoenix Award committee, it still does ring true after passage of time suggests that embodiment of elements from Space Age mythology evokes a deep response from contemporary readers, deeper than if imaginative elements alone were present. My personal imagination, after all, is not really very fertile.

But of course opinions differ about how an advanced galactic Federation must, or ought to, behave, and this was a major theme of the story. I don't believe advanced species interfere with less advanced ones, and my principal conscious aim in Enchantress was to counteract the idea that they do. I feel that how people view the universe, and our future relationship with inhabitants of the universe, is an issue that matters. In particular, it matters whether they believe superior beings from other planets will ultimately solve our problems for us, a hope that is taken seriously not only in space fiction but by many radio astronomers on one hand and by many UFO cultists and New Agers on the other. One of the most prominent features of Space Age mythology is this "Gods from Outer Space" theme. It's good in one way, in that it's a metaphor for the growing conviction that the universe is friendly rather than hostile. But on the whole, its social and religious consequences are somewhat disturbing. I think we can do without the naive notion of alien astronauts in the role of God.

Not everyone notices the extent to which space fiction has religious implications, and yet practically all of it does--this is one of its most striking aspects. Essentially religious premises underly almost all popularly-successful space films, whether or not they're identified as such. This isn't surprising; myth has always dealt with the same areas religion does, since such issues demand metaphor for expression. To be sure, the attitudes toward these issues in various space stories don't agree. Fortunately, ours is a heterogenous culture, and thus the tenets of Space Age mythology, in contrast to those of the mythologies of earlier cultures, are not uniform. There is no danger of their turning into dogma. But an author is compelled, more than in most forms of fiction, to deal with the subject implicitly if not explicitly.

At the time I wrote Enchantress, we had seen the film 2001, which openly endorsed the "Gods from Outer Space" concept, and the Star Trek television series, which did so more subtly by portraying humans who too often ignored their nominal policy of not playing God on alien worlds. I don't share this view, and I set out to present a different one. I didn't originally think of it as a religious issue. I did not, at first, recognize any of the religious issues in Enchantress, although when I read over the finished book I did grasp the implications of what I'd said about truth in metaphor. Only much later did I see that ESP and other psychic powers pervade space fiction as a metaphor for spiritual reality. This became most specifically apparent, of course, in the film Star Wars.

To sum up, space fiction as the mythology of the Space Age does for our culture what earlier mythologies did for theirs--though we can't fully compare them since we are seeing it in an early, undeveloped form rather than one that has stood the test of time. It explores our relation to the universe we inhabit, the sea of space that now confronts us as the seas of Earth once confronted ancient sailors. It explores the larger questions of our place in a cosmos of which Earth is no more the spiritual center than it is the physical one. And above all, it gives us hope for the future. One of the outstanding things about films based upon it is that unlike most others, they are optimistic, often even uplifting. In a world that many people perceive as depressing and/or terrifying, they are an island of light, illuminating our inner conviction that our destiny lies far beyond a single, isolated planet.

This is less noticeable in written space fiction because so many authors

try to be "serious," or at least innovatively imaginative, rather

than to portray their own real views of life in terms of the current

mythology that exists. I prefer to take advantage of that mythology. I

believe we should pay heed to what it shows about our instinctively hopeful

response to the new environment that awaits our species. If Enchantress

from the Stars has enduring value, then I believe it will be because of

myths upon which I unconsciously drew. The response to the book sustains my

faith in their power, and for this, I am thankful.

Copyright 1990 by JAI Press, Inc.; 1998 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.

This essay is included in my ebook Reflections on Enchantress from the Stars and Other Essays