Frequently Asked Questions

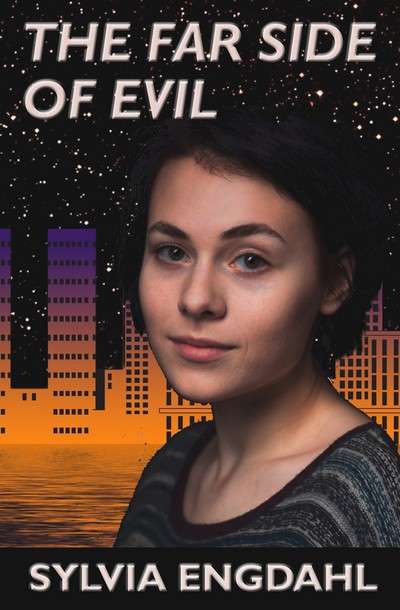

Firebird edition (2005)

Why did you make the second book ahout Elana so different from

the first?

I'd had the story in mind for many years, so I started writing it

as soon as I finished

Enchantress, and since it required interstellar

explorers with the same policy as the Service, it couldn't be about a

separate organization. I have since been sorry that I used the same heroine;

another agent of the Service could just as easily have been the protagonist.

None of the other characters from

Enchantress appear in it.

What age range did you have in mind when you wrote

The Far Side of Evil?

I intended it for high school age. In the era in which it was first published

there was no such thing as a Young Adult category; everything not published as adult

fiction was issued as a "children's book." Unfortunately, to my great dismay the

publisher labeled it "age 10-14" on the jacket because that was the age range that

sold best, and because

Enchantress from the Stars, which was popular, was

suitable for that age (though it too was originally meant for teenagers). I have always

regretted connecting

The Far Side of Evil so specifically to

Enchantress.

But when I wrote it,

Enchantress hadn't yet been published and I didn't foresee

that my books would be given to preadolescent children.

Why do you make such a point of saying that The Far Side of

Evil is not suitable for as young an audience as Enchantress from the

Stars? Some children have liked it at 10 or 11.

Some children even like adult science fiction at 10 or 11. Young readers

unusually mature for their age are not turned away by statements that they

are too young for a book. However,

Enchantress is often given to

average 5th and 6th graders, who enjoy the story even when they don't

understand as much of it as older readers do. These children (and teachers

who haven't read

Far Side) are apt to assume that the second novel

about Elana will have similar appeal, when it is actually a very different, and

much darker, story that only very exceptional readers below high school age

find enjoyable. Children may find its subject matter--torture, imminent nuclear

war--disturbing, or they may feel the discussions it contains are too

complex to be interesting. No author wants a book to be called "not as good

as the first one" simply because it was given to readers not apt to like it

as well as its predecessor.

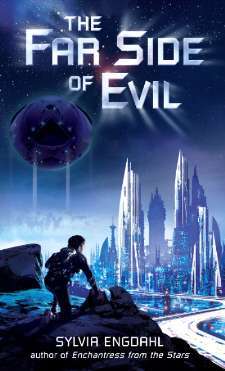

2018 edition

Especially when other readers may think it's better! Many older teens and

adults, especially those not attracted to fantasy, prefer

The Far Side of

Evil to

Enchantress. So the other reason I keep saying it's for

older readers is that teenagers often avoid books that are thought suitable

for younger kids. Not nearly as many teens have read it as might have done

so if it hadn't been called a sequel.

Why didn't you let the characters in The Far Side of Evil find

the key to the Critical Stage, the factor that causes some civilizations

to destroy their worlds instead of expanding into space?

I've been asked this since friends first read the book before it was

published, and my answer has always been the same: If I knew the key, I'd

tell the President of the United States instead of putting it in a novel!

(Recently, however, I've has some new ideas about the key, which are discussed in

my essay

Update on the Critical Stage.)

Does that mean you think the Critical Stage is real?

Why does anyone doubt it? I first developed the theory of the Critical

Stage in 1956, before the people of planet Earth had any space programs.

Then, as throughout most of the years since, the threat of nuclear war was

of great concern. It seemed to me that if we didn't turn our attention to

space soon, we would very likely destroy ourselves. One of the most

encouraging events I've ever witnessed took place just a year later, when

Sputnik was launched into orbit, making it impossible for the setting of

my story to be Earth. This does not mean, however, that the planet in the

story is simply our world under another name, because I believe what I wrote,

that the Critical Stage is a natural one that all inhabited worlds go

through.

The Far Side of Evil was first published in 1971, during the era

of the Apollo moon landings. At that time, I believed Earth was safely out

of the Critical Stage. It didn't occur to me that a planetary civilization

might cut back its thrust into space once it had gotten started. But that,

unfortunately, has been the case with ours. The delays and cutbacks in

Earth's space programs have been very alarming to me. (For more of what I think

about the Critical Stage, see

Space and

Human Survival and other essays at this website--including the

more recent

Thoughts on the 50th

Anniversary of the First Moon Landing, in which I express a more

optimistic view of the hiatus in space travel.)

Walker edition (2003)

In the early 70s, when many people wore Peace Symbols as pendants,

I went around wearing a Moon Landing medallion (one of many in a

collection I then had) because I truly believed that putting humanity's

energy into exploration and settlement of new worlds in space was the

only way to bring about lasting world peace. I still believe this! I

still believe that "We came in peace for all mankind" meant more than just

having peaceful intentions toward our competitors in the Space Race of the

60s. Although our world today is no longer so much like the world in

the story, there is peril as long as many nations, and many kinds of

troublemakers, are competing for the resources of one small planet.

Yet we still have wars even though we have space travel; doesn't

that invalidate the premise of the story?

No, because our civilization hasn't made a lasting commitment to a major

space effort. We are not established in space in any significant sense--we

have simply made some brief trips there and performed some scientific

investigation, and then failed to pursue more than a fraction of the space

undertakings of which our technology is capable. We've abandoned the moon.

We've built no orbiting colonies or even large-scale industrial facilities

in space. We've turned our backs on human exploration of Mars. As a

species, despite the dedication and enthusiasm of an all-too-small minority

of individuals, we are no more committed to expansion into space than we

were before we had launched a single spaceship. And so there's as yet no

evidence one way or the other as to whether the story's premise is true or

not.

Isn't the novel more about Earth's political conflicts than

about space?

Isn't the novel more about Earth's political conflicts than

about space?

Absolutely not. Some readers thought I used space fiction as a vehicle

for political commentary, whereas in fact I used political melodrama to

dramatize ideas about the importance of space. Beyond the obvious and

uncontroversial premise that dictatorship is a bad thing and totalitarian

rulers are motivated by desire for power, the story's main reference to

Earth's affairs concerned the youth activism of the late 60s--some of which

struck me as comparable to Randil's well-meant but disastrous attempt to

change the world overnight. This, however, was a side issue compared to my

conviction that expansion into space is the only way of eliminating war

on Earth.

Atheneum edition (1971)

Then are you sorry you portrayed a political situation that makes

some people consider the book outdated?

That's not what dated the original edition. The planet in

the story is comparable to Earth of the 50s, not the 70s; at the time of its

publication it wasn't meant to be a portrayal of current conflicts.

But the Critical Stage has turned out to last longer than the book suggested;

my assumption that the invention of space technology will cause a

civilization to immediately put its energy into a space effort has indeed

turned out to be invalid.

Furthermore, the Critical Stage has proved to be much more complex than

I imagined when I assumed it was merely a brief stage in our planet's

history. We now see that nuclear war is not the only danger; we face other

threats such as terrorism, biological weapons, destruction of the

environment, and depletion of our natural resources--to name only a few of

the problems that will eventually confront any civilization confined to a

single world. Some people think these disasters can be avoided by effort on

our part. I do not. I believe they are the natural consequences of our

species being ready to expand into a new and larger ecological niche. In

my opinion, the only way we can save Earth is to take up that challenge.

Isn't this too unconventional an opinion to be taken seriously?

Though I can't deny that it's a minority opinion, I am far from alone

in holding it. On my

Space

Quotes to Ponder page I have posted quotations from dozens of

people, including some very well-known people, who believe expansion into

space is essential to the survival and/or future welfare of our species.

Furthermore, in 2017 I added several quotations that specifically state the

importance of space to elimnation of war as epigraphs to the ebook and

current paperback editions of

The Far Side of Evil

Why do you now tell people not to read the original edition of

The Far Side of Evil?

Because the 2003 and later editions contain revisions to the story's

statements about the Critical Stage that have a major impact on their timeliness.

If you haven't already read the old edition, I urge you not to read an

old copy, because recent history has invalidated some of the wording I

used in 1971. I don't want the book to be less convincing than it

would be if read in its updated form, which makes plain that it's the

ongoing colonization of space, not merely the invention of space travel,

that's crucial to survival.

Collier editiion (1989)

But in Enchantress from the Stars, colonization is shown

as wrong.

Only because the Empire in that story colonized

inhabited planets,

which as I've said in the FAQ for

Enchantress, I don't believe would really happen.

Once, the idea that spacefarers might colonize inhabited planets was plausible because

of past history, but we have progressed; even today, no one in charge of space policy

would consider doing such a thing, so more advanced civilizations surely wouldn't.

That's one of the reasons I regret having connected the two books--

Enchantress

is based on both traditional and recent mythology, whereas

The Far Side of Evil

is meant to be taken more literally. (When Elana discusses colonization in the revised

edition, I wish she could say that civilizations advanced enough to build starships never

colonize inhabited planets; but she can't because of her involvement in a story

where it happened.)

Incidentally, I disagree strongly with the view held by some people that the term

"colonization" should not be used in connection with space because of its negative

political connotations. This objection strikes me as invalid and in fact ironic. On Earth colonization

involved taking over the land and/or culture of indigenous inhabitants--but that is precisely what

a space colony would not do! Nobody, to the best of my knowledge, advocates colonizing

inhabited planets, even if we should ever find any. The idea of expanding into space is to

abandon our dependence on zero-sum games and thus avoid any more takeovers. A more

accurate precedent for the term "colonize" in the space context is its meaning in biology: the

establishment of a species' presence in a new ecological niche.

Did you change anything in the 2003 edition besides

the discussion of the Critical Stage?

The action of the story hasn't been changed in any way. I removed

non-inclusive (sexist) language, and made many other improvements to

wording--some I'd long wanted to make and others suggested by my new

editor. It is now a better book as well as a more timely one for today's

readers.

For more information about the updating, read the

Afterword to the 2003 Edition

Why isn't the 2003 edition labeled "revised" on the book itself

or in catalogs?

The Library of Congress doesn't consider an edition "revised" unless

20% of it has been altered. I didn't change

that much! In my

opinion, the wording changes, though minor in terms of length, were of

major enough significance to announce, so that people who read the

old edition or were considering buying used copies, would realize that the newer

one was worth getting. (By now, of course, this isn't a problem since few copies

of the 1971 edition still exist.) But Walker chose not to say anything about updating in

their publicity, so it's mentioned only in the new Afterword and on the

jacket flap.

>

British editiion (1975)

No. The text of the current edition is the same as the 2003 and 2005 editions

and the 2011 ebook (except for a few very minor changes to mentions of the Service

that I made for consistency with my more recent Captain of

Estel trilogy).

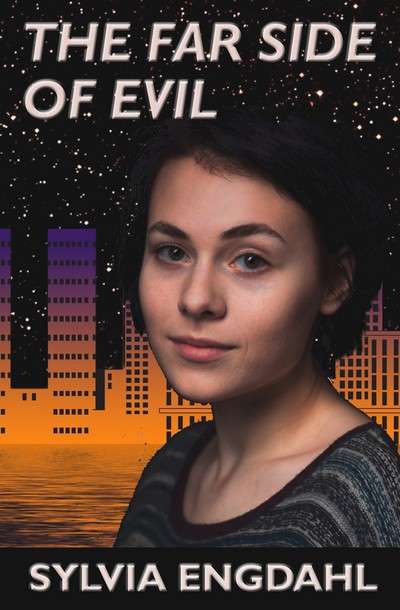

This is the first time I personally, as distinguished

from a publisher's artist, have ventured to portray Elana. In the two books about her I

carefully avoided saying what she looked like, since the question of whether she's

descended from people of Earth is meant to be an open one. But most of the other editions'

covers have shown her in one way or another, so I decided to offer my own visualization,

and I have chosen a cover picture that suggests she is of mixed Terrestrial race. (For more about this, see the FAQ for

Enchantress from the Stars.) Of course,

in this book she is older and in a darker situation than than in

Enchantress from the

Stars, so she looks different from what readers of that book may have imagined.

What do you think the changes in our world since September 11,

2001, mean in terms of our own Critical Stage?

Several people wrote to ask me this. I'm sorry to say I think the

growing problem of international terrorism is exactly what can be expected

in a Critical Stage civilization: one that has outgrown its home world but

has not yet directed its energies into moving beyond, and in which the evil

actions of a few individuals can affect the entire planet. Yet in one way

this is a hopeful view; it reflects my belief that the threats we face are

not signs of something having gone wrong with our species' evolution, but

natural ones against which we must develop defenses, as we must against

other natural disasters. I believe we will win the war against organized

terrorist networks, just as we got through the crises of the second half of

the 20th century--all of which I remember personally. I don't think the

world is in any greater immediate danger than it has been since the 1950s,

although the American public now has a new awareness of peril. But

time is running out (again, see my

Space and Human Survival page). To let the current situation

distract us from developing space technology would, in my opinion, be

self-defeating.

Added November 2, 2006: Recently, my view of this issue has changed

somewhat. I now feel that the world will soon be in greater danger from

terrorists than in the past because they will have access to emerging new

technologies such as biotechnology and nanotechnology, with which they could

do great harm. These technologies offer many benefits to humankind and I am

certainly not opposed to them, but they could be used destructively by small

numbers of people. Therefore, it's important that defenses against them be

developed before they are made available, and it's more imperative than ever

that a space colony be established as insurance against disaster.

For more of my opinions about space, be sure to visit the Space section

of this website (click the Space tab at the top of this page). Most of the material

there is also in my ebook From This Green Earth: Essays on Looking Outward,

which is availalble in ebook, paperback. and audiobook editions,