The Future of Being Human

by Sylvia Engdahl

This is the title essay in my book The Future of Being Human and Other Essays.

*

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

-- Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, Les Guêpes, 1849

That this French aphorism, usually translated as "The more things change, the more they stay the same," expresses a commonly-recognized truth is shown by the fact that googling the English version yields 509,000 hits. It is most often said cynically, especially in political contexts, to mean that despite reforms nothing ever gets any better. Yet it is also used to say that people's basic wants and fears don't change even though as time passes they involve different situations. Or it can refer to surprise at finding that despite change in one's outlook some things, usually tangible things, have remained constant. Philosophically, it can mean that apparent changes do not affect reality on a deeper level. And I have recently discovered that the phrase is in the lyrics of a variety of pop songs.

I think, however, that it is especially appropriate as a description of the very nature of human beings. From era to era, there are enormous changes in human cultures and human technologies--but human nature does not change. People are people, in whatever era they happen to live. Our present way of living and the technology that makes it possible would be utterly incomprehensible to the ancient Greeks, yet if we met them as individuals, we would find them much like ourselves. Similarly, if we were to meet the people of tomorrow we would have feelings in common with them even if their appearance and lifestyles seemed strange.

Until recently, this was taken for granted. But now, speculators about the future are saying that future humans will be so unlike ourselves as to seem, or even literally be, a different species. A friend once wrote to me, "The next generation of human evolution is about to take place in the next century instead of the next million years. They aren't going to be like us, and I actually believe there won't be an ‘us' much longer (in historical time)."

This strikes me as a profound misunderstanding of what it means to be human. Setting aside semantic difficulties with the word "evolution," which I'll deal with below, such suppositions are usually based on the fact that technology is enabling us to make changes in our bodies and more and more drastic physical changes are on the horizon. But is our humanity defined by the appearance, or even the capabilities, of our bodies? Surely not. That assumption flies in the face of all the progress toward tolerance we have made.

In the nineteenth century and even into the twentieth, "scientific" anthropology held that skin color marked races as inherently different from each other and that dark-skinned races were inferior. Some called them a "missing link" between humans and apes. Most of us long ago condemned such views. More recently, we have abandoned the once-common prejudice against the disabled; we do not consider a person with missing limbs less human than the rest of us. Why then would alteration of the body make us question someone's humanity?

People with disabilities are no longer vewed as different from other humans, and future changes in human bodies won't affect our humanity, either..

So far, it has not. People with medical implants such as pacemakers, artificial hip joints, or brain electrodes to treat epilepsy are not viewed as semi-human. To be sure, these devices are not visible, and some readers will protest that they merely restore normal functioning rather than improve it. But in principle there is no difference. We don't think of wide variation in genetic endowment as defining degree of humanity; an Einstein and a person with Down syndrome are viewed as equally human although not equal in mental capacity. A star athlete may be admired more than someone born lame, but the humanity of the latter is not in doubt. If it becomes possible to increase abilities, either mental or physical, where could a dividing line be drawn?

It's sometimes asserted that genetic or neurological technologies will produce not merely a line but a wide gap. But will people want that? Technology can't spread on its own; it is developed beyond the experimental stage when, and only when, it serves human needs and/or desires. Mere technological feasibility is not enough to bring about new developments; they must be wanted by the public. In the 1940s popular speculation about the future held that someday we would all have personal helicopters parked in our yards. The technology for personal helicopters was clearly on the horizon. Why don't we have them now? Because a neighborhood full of helicopters is neither practical nor desirable. On the other hand, personal computers-- which we didn't imagine even in the 1960s--are useful; they provide capabilities that people want to have. Undoubtedly countless more useful things will be developed in the future. But fundamental human wants aren't going to change.

We now see it's likely that people will want improved bodies. But comparatively few of them will want to be transformed into a new species or to be replaced by cyborgs. Human relationships will always be important to them, and most people have a strong emotional attachment to their physical form and that of their loved ones. Moreover, they don't want to be seen as different from everybody else--they want to enhance physical characteristics that are already admired.

Thus it is difficult to imagine any major changes in the human physique that would be marketable. Many of the things often envisioned are pointless. Movies and TV series that show super-capable individuals are good entertainment, but they have little relationship to what would be useful in real life. We don't need people to be strong enough to lift a car or jump ten feet in the air, or to fly, or to be efficient killers like Terminator. These are anachronisms; we have technology to do all the physical things that might have been helpful to our ancestors. We don't need to become human computers, either. One of Robert Heinlein's YA novels features a mathematically gifted young man who keeps starship astrogation charts and tables of logarithms in his head; this proves so valuable that although he has no space experience whatsoever be becomes captain when the original captain is killed. At the time that was written it would have seemed desirable to give human beings such capabilities, but now it would just seem silly. We have computers for astrogation; there are better things to occupy human minds.

I've seen it argued that people will be eager to change their bodies because they now want weird piercings and tattoos. Yet there have been cultures that admired weird piercings and tattoos since the beginning of time; in some African tribes it was a status symbol. In ours it has become fashionable, but fashions don't have a lasting effect on the human race unless they are heritable. Some currently-fashionable features, such as being thin, will probably be made heritable through genetic engineering, if that proves possible (which it may not, as the science of genomics is finding that far more factors than genes affect a person's biological characteristics). But there's a limit to what people will want passed on to their offspring. How many now have their babies tattooed, or encourage their young kids to get piercings?

People won't want changes to their bodies made heritable. After all, though tattoos are increasingly popular parents don't have small children tattooed.

DNA technology will undoubtedly be useful--but hardly for such extreme changes in human beings that they would no longer be "us." It will be employed for medical purposes and perhaps for producing "designer babies" with the particular characteristics their parents choose from among normal ones. It may be able to provide some enhanced mental capabilities, though these are more likely to be produced by neurotechnology. But why would anyone want intelligent beings entirely different from us? Scientists might want to prove they could create them, but such beings would have no adaptive advantage. Mere change is not evolution. Evolution occurs when new capabilities enable an organism to adapt to its environment better than its predecessors. We have, or will have, technology to do everything our environment requires; we have no reason to alter our offspring in any fundamental way.

When it comes to colonizing other planets, we might well wish to modify our bodies to fit new environments. But there is no reason why this would result in separation into different species--after all, dogs of widely varying size and shape are all the same species and can interbreed. Inability to interbreed and produce fertile offspring is the determining factor in speciation, and appearance, within obvious limits, has nothing to do with it. Why would humans choose to alter their DNA in such a way as to prevent interbreeding? In nature division into different species requires separation for very long periods of time; it could not occur within the time frame of any imaginable future unless it was intentionally engineered. And it's unlikely that humans of different types would refrain from sex with each other.

Might not mutations caused by exposure to radiation in space lead to eventual genetic differences? No, because even if no way to prevent such mutations is found, before we have a significant number of people in space we will be able to correct genetic damage or at least detect it so that it won't be passed on. Only if some disaster were to destroy civilization on Earth would there be danger of widespread heritable mutations, in which case anything now said about the future would become meaningless.

There is another reason why society won't encourage drastic changes to human bodies. We have had more than enough trouble with race relations, even among members of the same species; to invite similar conflict would go against deep moral convictions as well as against common sense. To be sure, there may be persecution of people who have, or don't have, particular characteristics. Very probably it will get worse if some are given heritable abilities that others are not. But it won't be a matter of "us" vs. virtual aliens.

Fear of laboratory-produced pseudo-people has been around a long time; it's no accident that the story of Frankenstein struck a chord and is still popular. When the first use of in vitro fertilization (IVF) was announced there was doubt as to whether the baby would become a normal person. And remember the excitement about clones a few years back--the media promoted the idea that clones would be inhuman; some speculated that they wouldn't have souls, when in fact a healthy cloned person is no more "different" from the norm than is a naturally-born identical twin.

People have long been horror-stricken by the idea of scientists unintentionally creating an evil artificial human.

It's unlikely that human clones will ever be produced even if it becomes possible to do it safely, because it is now evident that nobody wants them--a whole list of potential reasons people might want clones was suggested, but none of them had adherents. There was once a waiting list for cloned cats, but when it was found that they didn't have personalities just like the cats they were cloned from, interest died down and the company producing them went out of business. [A new company is now cloning pets for high prices, but owners who expect them to be identical are disappointed.] Clones are useful in agriculture, but there's no market for the technology apart from that. History is full of theoretically-feasible developments for which there proved to be no market.

Modification of bodies won't be the only future technology viewed with dismay. All major technological innovations have aroused fears that they would diminish our humanity. Plato deplored the invention of writing because he thought it would weaken people's memories. John Philip Sousa argued that the phonograph would result in loss of the ability to create music. As late as the 1970s, I knew people who believed the use of computers by banks and for billing purposes was dehumanizing. More recently a great deal has been written about how screen time and texting will supposedly make kids less able to interact socially, a fear no more warranted than the earlier ones. Such worries are groundless. People are people. Their customs and living conditions change, but human nature doesn't.

*

Nevertheless, do we not speak of the future evolution of humankind, meaning progress of some sort? That depends on how the word "evolution" is being used. There are two forms applicable to humans. The first, biological--i.e. genetic--evolution, was until recently thought to have ended for our species in prehistoric times when technology enabled us to adapt to changing environments and individuals not well adapted no longer died before they could mate. Genetic sequencing technology has now shown that it is still occurring; but it is producing only minor changes in certain groups, which do not affect the overall evolution of humankind. In any case biological evolution does not necessarily mean progress, a judgmental word that implies improvement. Although most of us would call the evolution of humans from an apelike ancestor progress, to biologists evolution is simply change.

The second form of evolution is cultural evolution--or extragenetic evolution, a term now preferred when referring to our species as a whole because it's less easily confused with the evolution of specific cultures. This is the only form of human evolution that's significant now. Although to me and to many others it implies progressive change--change for the better--not everyone agrees. Social scientists and philosophers have argued at length about the concept of human progress, and whether it can be said to occur is a controversial issue. However, the controversies generally concern definition of what constitutes progress, with those of various political persuasions disagreeing. When I state or imply progress in connection with evolution I'm referring to a common-sense definition, applied to our entire species. For example, there can be no doubt that the invention of agriculture and the development of language in prehistoric times was progress, and it was certainly progress when we abolished chattel slavery.

Progress of humankind occurs over long periods and can be judged only by looking backward. The development of tools during the Stone Age was unquestionably progress.

Extragenetic evolution is the result of new ways of doing things, not the cause. It is cumulative from generation to generation. Because of what we have learned from our forebears over long periods of time, we have more capabilities than our remote ancestors and are able to develop skills they could not have developed. Whether this is entirely a matter of recorded information and of the young being taught by adults is, in my opinion, an open question. I personally believe some form of "collective unconscious" must be involved. (See my essay "The Role of Psi in Human History.") Surely mere teaching by a time-traveler would not have enabled teenagers 5000 years ago to drive 70 miles an hour on a freeway or to program computers, although biologically they were indistinguishable from people today and possessed complex skills that we lack.

Whether or not such changes are considered progressive, our planetary civilization does progress. It enables more and more people to survive, most of them more comfortably than was possible for previous generations; it accumulates knowledge; and over time, its predominant moral standards become increasingly peaceful and humanitarian. In my novels I say a good deal about progress or maturation of culture-bearing species, terms I often use interchangeably. However, this does not mean that individuals of a culture at one stage are different from those at another, though they may behave differently depending on the characteristics of that culture. In Enchantress from the Stars and also in my other books, the people of young species are portrayed as equals of the people of older ones, despite having fewer capabilities and less knowledge.

Incidentally, this brings up another semantic issue: are extraterrestrial races "human"? Obviously they are not members of our human race, and in this essay I am dealing only with ours. I'm not in a position to know anything about whatever others may have evolved elsewhere in the universe, but In my opinion they are the equivalent of humans however different their biology may be, and whether they're referred to by that word in fiction is just a matter of terminology.

On a planetary basis human evolution involves advances in technology, although not all cultures of a world need be at the same technological level. There are many such levels, from primitive tools to steam-based industry on up to spaceships and artificial intelligence. What they have in common is that they enable people to adapt to their environment in ways that increase their ability to survive and multiply. That's why extragenetic evolution has supplanted genetic evolution--it is the fastest, and often the only, means of ensuring survival and/or increasing the population. Primitive humans could not have survived without tools and cold-weather clothing. Later humans could not have survived in large numbers without agriculture, machines, and weapons. And we cannot survive long in the future without space technology that enables us to utilize extraterrestrial materials and eventually colonize new worlds.

But once a level of technology is reached, people use it in ways not related to survival. They use it to get things they want. And these uses often lead to major changes in their customs and daily lives, sometimes of unpredictable kinds. In the twentieth century people wanted fast, convenient transportation, and the automobile transformed society. They wanted housework to be easier, and appliances freed women to have careers. They wanted easy access to news and entertainment, and television revolutionized their interaction with the world beyond their local areas.

In this century the Internet and cell phones have caused a dramatic difference in the way we conduct our lives. So what comes next? If we're not going to become superhuman, as I believe we're not, where will extragenetic evolution take us?

*

Some "smart-home" AI technology is already available and far more complex devices will be developed in the future.

It's generally agreed that the next big change will come from the rapidly increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI). More and more things used industry and by the public will be automated in the near future. Homes will have robotic vacuum cleaners, floor scrubbers, and self-cleaning plumbing fixtures. These and basics such as light, heat, and cooling will be controlled not only by voice command but by programmed scheduling, as will most kitchen appliances. Security devices will screen people at the door, both residents and visitors, by facial recognition and will lock and unlock the house when appropriate without the use of bolts or keys, calling the police if an intruder is detected or paramedics if an occupant's actions indicate a medical emergency. The disabled, the elderly, and children of school age will be safe when home alone, freeing caregivers to work part time or do errands.

There is just one commonly-predicted type of household AI I believe we will not have--robots shaped like humans. What would be the point? I can't imagine their being useful compared to the many other forms artificial intelligence will take. An exception must be made for sex robots, since life-size sex dolls with silicone skin are already on the market and selling well, with AI models expected to be available soon. Some psychologists are endorsing the concept, while others deplore it, and one Japanese company has banned having sex with its products--though it's hard to see how such a ban could be enforced. However, I think the average person is going to feel that sex is one activity in which automation would be of little benefit.

Elon Musk, CEO of both SpaceX and the automaker Tesla, has said that by 2037 owning a car that isn't self-driving will be like owning a horse today. My first thought was that this overlooks the fact that if a dramatic increase in AI-controlled devices and manufacturing leads to widespread unemployment, as it undoubtedly will, a lot of people won't be able to afford self-driving cars. But will they need them? Actually, once self-driving vehicles are common the average person won't own a car at all. Without the need for a driver the price of Uber-like services will drop. Why would anyone incur the expense of buying, insuring and maintaining a car when self-driving robotaxis, summoned via a mobile phone, can take people wherever they want to go without the problem of finding a place to park?

Self-driving vehicles will have a far greater impact on daily life than is first apparent. Besides robotaxis, there will be self-driving delivery trucks, and no one will have to spend time and energy on shopping. It's already possible to order from supermarkets via the Internet for pickup, and in some cities delivery is available. This will become standard everywhere when it's no longer necessary for stores to pay a driver. In the days before automobiles were common, groceries were delivered routinely; milk delivery was the last to be discontinued. Now, almost everything else--even prepared meals--can be bought on the Internet, and though the popularity of food delivery is growing, the transportation cost is high. Other online purchasing is also limited by the cost of shipping. Self-driving vans will lower these costs to the point where it will be less expensive, as well as less time-consuming, to order online than to go to a store. Eventually there will be no need for shopping centers, so traffic will be less congested and there will be no ugly parking lots or big-box structures.

Eventually self-driving cars and robotaxis will result in major changes in people's way of life, just as the automobile did in the early 20th century.

Furthermore, without the time lost in traffic jams and parking, people will be able to live further from what business districts remain, in less crowded areas with more green space. Commuting will be done by robotaxis, of course, though there won't be as much commuting because more people will work electronically from home offices. Commuter trains will continue to exist as long as there are centralized destinations, but with little need for workers below the managerial level, companies will move out of congested areas. In time, cities as we know them will be a thing of the past.

Long-distance rail transportation, too, will be automated and if speeded up by new technologies, it may make a comeback once population increase causes air traffic to become so heavy that there are long delays. When people want to take trips to out-of-the-way places by car, they can rent a self-driving one. Assuming that automated vehicles are designed and tested for safety, once all human-driven cars are off the road there will be few if any accidents--and no worry about drunk drivers. Even a small percentage of self-driving cars will save countless lives.

Another coming convenience will be the routine use of telemedicine. Electronic transmission of medical data and remote face-to-face contact with doctors is currently used by people in rural areas, but as technology advances and AI is incorporated, it will become routine for everyone. Medical facilities will be used only when hands-on care or special testing equipment is required. On the positive side, this will eliminate most trips to healthcare providers and the waiting involved, make it unnecessary for people to leave their homes when they feel sick, allow them to consult specialists in distant cities, and permit constant monitoring of chronic conditions. On the negative side, it will lead to ongoing surveillance of everyone's physical status, which will be a serious invasion of privacy

But won't people feel more isolated when nearly everything essential to living, apart from certain jobs, can be done without leaving home? Not necessarily--after all, we now rely heavily on cell phones and online social networks, and these channels of communication will in the future provide two-way interaction on large screens or perhaps in 3D. In fact, life-size holographic 3D video-conferencing technology is already in the experimental stage. Although people have an innate need for human contact, the essence of it, apart from intimacy within families and between lovers, lies not in proximity of flesh but in exchange of thoughts and emotions. When telephones first became available skeptics feared that the ability to talk over a distance would make lead to a loss of sociability, when in fact the opposite occurred; people today hear the voices of friends all over the nation instead of just those living nearby, and many spend more hours talking than would be possible if they were limited to face-to-face contact. And online networking makes it possible to have far more personal acquaintances than could ever be met in person.

Moreover, opportunity for face-to-face contact will not be lacking. Robotaxis will make it easier to attend sports events and gather for parties in homes or restaurants, especially since with no need to drive, social drinking won't be a problem. Recreation centers will proliferate, many of them in scenic areas, offering food and fellowship as well as facilities for swimming, sports, hobbies, and stage shows. Outdoor group activities such as picnics and live-action role playing games will be popular.

Through virual reality, people will be able to socialize or play games with distant friends all over the world.

There will also be expansion of new forms of home entertainment, notably virtual reality (VR), now an available enhancement of video games. Participation in online multiplayer gaming will increase; it is now limited by the time it consumes, but in the future more people will have leisure, and there will be greater variety of game scenarios--they don't all involve violent action, and in fact some depend on cooperation between players rather than conflict. It's expected that in the future some VR games will be played via computer/brain interfaces rather than helmets. I'm skeptical as to the number of people who will want brain implants, but it's wise to be cautious in such predictions--in 1916 silent film icon Charles Chaplin said "The cinema is little more than a fad," and In 1946 studio executive Daryl Zanuck declared, "Television won't be able to hold on to any market it captures after the first six months."

The prospect of AI-assisted living is exciting, but there is a downside and serious problems will have to be solved before it can benefit everyone. In the first place, there is likely to be economic and social upheaval due to loss of jobs. When all vehicles are self-driving, truck and taxi drivers will find themselves unemployed, as will workers in many other fields who are replaced by AI. In the past technology that eliminated jobs has always led to new kinds of jobs, but that won't happen if AI takes over all routine work. There will be jobs at the managerial and professional levels and for work demanding creativity, but few for blue-collar or office workers. Most experts agree that the immediate effects are likely to be devastating.

It's easy to say that the government should subsidize unemployed workers, but if hardly anybody is working, then who will pay the taxes that support the government? It has been suggested that companies that got rich selling AI-controlled devices should pay, but when few people can afford to buy those items their producers won't remain rich for long; some may even go out of business. Thus use of AI won't spread as widely as technology permits, and for this reason the worst problems may be self-limiting. But there is bound to be a long period when some people aren't working while others are well-off, resulting in protests and political turmoil. At the very least the work-week will be shortened and we will have to adjust to a society that provides more leisure--something most employees will welcome.

However, too much leisure also has a downside. People generally find meaning in their work--or if it's mere routine, at least it provides structure to their days. And that is necessary not only to their own health but to the health of society. Those who are not working at least part time need some other source of meaning, something to which they feel committed. Where are they going to find it?

When AI takes over all routine work people will have time to enjoy art, music, and being outdoors.

One way is through volunteer work. There will be many opportunities to help others; for example, as more and more tasks in hospitals and nursing homes are taken over by AI, the patients will have a need for human contact no longer provided by nursing aides. Elderly people who live alone will need companionship--as they do now, when there aren't enough volunteers with time to offer it. Schoolchildren taught mainly by AI will need tutoring and encouragement by live role models. Pets in veterinary clinics or boarding kennels whose physical needs are met by machines will need love and companionship from humans. And there will be various humanitarian and political campaigns to work for.

Another major source of meaning will be competition, not only in sports but in skill contests such as talent shows and multiplayer games. People like to excel and the effort to do so consumes a great deal of time and energy. Participatory sports will receive more emphasis than in the past, with both kids and adults who aren't star athletes receiving some sort of recognition. Music and the arts will flourish; a market may even develop among the wealthy for handcrafted goods created by enterprising artisans.

Adult education will hold the interest of those with inquiring minds, and it may become common to earn college degrees unrelated to career aims. Finally, more and more people are finding meaning in spirituality--not so much in traditional religions, which are declining in most countries, but a sense of connection with something beyond worldly concerns. The popularity of meditation is growing. Deep commitment to groups centered on spiritual beliefs is important to many.

There will be no lack of options for becoming involved in tomorrow's world. To be sure, some will fail to take advantage of them, but that is true today; it cannot be blamed on advancing technology. In the long run, new technology is always beneficial to humankind, disastrous though it often is to people with training and experience applicable only to older technologies. The nineteenth-century Luddites feared being replaced by the rise of factories. Yet factories weren't detrimental to society, and ultimately they led to better living conditions for the average worker. The history of technology shows that new technologies invariably open up more opportunities than previously existed, and that despite working fewer hours, people have fuller lives as well as material possessions that far exceed any their ancestors imagined.

*

Paradoxically, the future will bring both greater freedom of choice and new restrictions of it. Such restrictions will be the inevitable result of increased government surveillance of people. AI will lead to extensive recording and analysis of information about individuals and their activities, which in turn will cause limits to be placed on actions deemed undesirable. Implanted microchips are already in use on a voluntary basis; while they can't yet track location, that capability will soon be added, and they may not remain voluntary. Some surveillance will be unavoidable in view of the growing danger from AI-equipped criminals and terrorists, and hopefully, safeguards will exist to prevent misuse of the data collected on innocent citizens. But the government's definition of "misuse" is unlikely to match that of privacy advocates. I have discussed this issue in my essay "The End of Personal Privacy."

China already uses robots in its courts to explain the law and advise people on what attorneys could best handle their cases.

AI is expected to streamline administrative and judicial proceedings; there will be no more long delays for permits or in the courts, and in principle at least, justice will done more equitably as well as faster. Some feel that the use of "robojudges" would eliminate inefficiency, prejudice, and corruption, and would thus be more fair than the current system. It might be, yet on the other hand, enforcing the letter of the law could lead to injustice in cases where extenuating circumstances would be considered by a human judge. Also, it might result in the proliferation of laws concerning minor offenses that ought not to be punished at all, especially if fines were a significant source of government funds.

Despite government intrusiveness, the personal choices available to individuals will continue to multiply, as they have for the past century or more. The selection of consumer goods, already vastly larger than it was before the Internet made it possible to market items appealing only to small segments of the population, will increase further as AI causes production costs to fall. And there will be a greater variety of leisure activities when more people have time to pursue them, as they will no longer need to suit the majority to attract participants.

One likely result of the growing demand for choice will be an end to cable and broadcast television. Already more and more people are switching to streaming TV, and now that the technology for it is widely available, it makes no sense to present new episodes of a series at a given hour in "prime time" expecting that viewers will watch them at that time. Eventually such scheduling will be abandoned and weekly or seasonal releases of all shows will be made simultaneously. Live newscasting will be available only via streamed video, and broadcast frequencies will be freed for the increasing use of wi-fi.

There will be far more significant changes than these in human society. The rights of women and minorities will be firmly established and no longer considered problematic. At least in Western nations, traditional views of morality won't be forced by law on individuals who disagree with them, and the public controversies concerning them will die out when it becomes apparent that it is impossible as well as wrong for one group's beliefs to be imposed on another. For example, abortion will cease to be a political issue, although citizens' personal views of it will continue to differ widely.

I foresee an end to our antiquated marriage laws, which are a holdover from the era in which wives belonged to husbands who had a legal right to control them and a legal obligation to support them. Since women are no longer dependent on men, marriage will become a wholly social and/or religious institution. Wedding ceremonies will be the same as today, but no license from the government will be needed to enter into a marriage or to end it--instead, couples will sign contracts with each other containing whatever mutually agreed-upon terms they wish. There will be no legal or tax distinctions between married and single people. In my opinion the problem with same-sex marriage is not that same-sex partners lack the privileges of heterosexual partners, but that the latter have benefits and privileges that there is no reason for them to have merely because they are in a committed sexual relationship. People who want to live together will do so, whether they have such a relationship or not, and they will part when they wish to part--that's how it actually works now, regardless of legal formalities.

People will get married just as they do today, but they won't need a license from the government and won't have a different legal status from singles.

The government will, of course, continue to control the guardianship of children, whether or not their parents are married. With the rise of nontraditional families and technologically-assisted conception as well as reliable birth control, genetic parenthood will be given less weight than in the past. The birth mother will be presumed to be the primary guardian unless she has relinquished that right or has a written agreement with the genetic mother. Normally couples' wedding contracts will include shared guardianship of any children they have together, but where no such provision exists, the husband will have no rights or financial obligation unless he has formally adopted a child. Whether there will be tax benefits for guardians--or conversely, a tax on children in excess of two--will depend on the economic situation of society and the degree of concern about overpopulation.

There will be a significant reduction in crime brought about by the legalization of all drugs. The only way to stop the violence associated with drug use is to take the profit out of dealing--a lesson that should have been learned from the failure of Prohibition in the 1920s. Once there is no money to be made selling street drugs, the police can stop spending funds on useless enforcement attempts and crack down on users who commit crimes while under their influence. That applies to prescription drugs as well as currently-illegal ones; at present painkillers bring a high price on the black market and tragically, low-income elderly people who need cash are being targeted by dealers as a source of them. Moreover, the high price of necessary drugs, a serious problem for low-income people, is due to the medical establishment's control of the supply. It was legal to buy medical drugs without a prescription until 1938, and that is one case where "turning back the clock" will be an advance.

Another badly-needed reform is the elimination of imprisonment of nonviolent criminals, which AI will make possible. In the future prisons will be used only for protecting society from individuals who pose a threat to the public. Lawbreakers who are not dangerous will be electronically monitored with AI devices--possibly temporary implants--that report their location and sense whether they are carrying weapons. Some may be placed under house arrest except for work, and will be restrained by shocks from the devices if they fail to comply. There will no longer be any reason why they should live at the taxpayers' expense under the influence of worse criminals.

Taxes, of course, will continue to be a burden--how great a burden will depend on how much aid to the unemployed proves necessary. In America it will also depend on the nature of changes to our healthcare system, which everyone agrees are long overdue. It is unlikely that it will get the kind of overhaul that is really needed, which is the elimination of unnecessary tests, procedures, and allegedly preventative care except for people who insist on them and can afford to pay personally. So there will probably be some form of single-payer system such as other nations have, which I personally would favor only for emergency care, treatment of seriously disabling conditions, and long-term care of disabled people who have no other source of support. Whatever else happens, the concept of health "insurance" (other than insurance against catastrophic illness) must be abandoned--what would fire insurance cost if everyone were expected to have a fire sooner or later? In my opinion ordinary healthcare expenses should be met by voluntary subscriptions to individually-chosen levels of service. But this may be one of the areas in which choice is reduced rather than increased.

*

However healthcare is paid for, it will offer life-changing new benefits to people who are sick or disabled. For one thing, DNA technology will be used for eradicating genetic diseases, treating some types of illness and injury, and possibly to lengthen lifespan. It will make it possible to grow replacement organs, eliminating the need for transplants from donors and lifelong dependence on drugs to prevent their rejection--or even to replace missing limbs. It may eventually provide a cure for cancer.

Nevertheless, there are inherent limitations on what genetic modification can do. There is no such thing as a genetically-perfect body. Genetic makeup involves trade-offs; a gene needed for one characteristic may adversely affect another, and few if any characteristics are determined by single genes. Moreover, genes interact not only with each other but with prenatal environment as well as with a person's later experience--it is now known that gene regulation is more significant than the genes themselves. The science of genomics, which studies these interactions, has proved to be far more complicated than was thought even a few years ago. Then too, people disagree about what qualities they consider imperfections. It is questionable whether any gene can be called "defective," except the rare ones that lead to death in infancy or early childhood. The idea of universal physical perfection arises from the timeworn notion that bodies are simply biological machines.

Furthermore, not all illness is of genetic origin and the more that is learned about defeating specific conditions, the more evident it becomes that eliminating one simply leads to another. In my opinion the state of a person's health, apart from rare genetic traits, accidents and virulent infectious disease, is controlled by the subconscious mind; preventative action can influence which illness that person gets, but not whether he or she stays well. Although the effects of the mind on the physical functioning of the body will in time be understood by science, that doesn't mean psychotherapy can alter them, as many such effects are not malfunctions but the normal genetically-programmed reactions to situations different from those they evolved to deal with. Therefore, medical science will never be able to make everyone healthy, and as I've said in my essay "The Need for a New Outlook on Healthcare," overtreatment of minor conditions usually does more harm than good.

A new type of prosthetic arm developed in Sweden is a big improvement over former types because it is brain-controlled and allows the wearer to feel sensation from it.

Neurotechnology is likely to surpass genetic technology as a means of medical intervention. There will surely be great advances in the use of brain implants to restore hearing, sight, and other functions to the disabled. They are already being used by patients with epilepsy and other disorders, and it is expected that they will eventually enable paralyzed patients to walk again. Experimentally, totally paralyzed people have been able to control computer cursors and robotic arms by thought alone, and progress toward elimination of physical disability will continue.

Even more significantly, it may become possible to reverse dementia with such implants--or at least to improve memory, a goal on which considerable current research is focused. Age-related dementia is one of the most serious problems facing our society. People over age 85 have a 50% chance of developing it at some time before death, and as medical science extends life expectancy, the odds of an individual eventually suffering from it will increase. It can mean devastating loss of the memories of everything that has ever mattered to that person, as well as of the ability to function in daily life. Moreover, most families are not in a position to provide full-time care, yet the average cost of living in a nursing home is now nearly $90,000 annually. Since few of the elderly can afford this for more than a short time, the government must pay; and economists now fear that as the number of people affected grows, not enough money will be available. If a cure for dementia were found it would benefit not only its victims but a large share of the population. So far, no drugs have proved useful. Perhaps the answer lies in neural modification of the brain.

The extent to which brain implants are used for enhancement of normal capabilities depends on how useful people find them. Personal memory improvement will be desirable, but I doubt that there will be much demand for neural interfaces with computers except for short-term learning of specific subjects and for gaming. A permanent ongoing connection with the Internet strikes me as dangerously intrusive, but perhaps I'm influenced by my feeling that personally I wouldn't want to be a cyborg. In any case, I do not believe that such changes would significantly alter people's personalities.

Apparently, from what I read, there are people who do want to be cyborgs and replace all or most of their bodies with electronics. They might have second thoughts if the technology became available; it's one thing to speculate for fun, and quite another to actually undergo such a transformation. It would be their right to do so if they were willing to pay for it--but I don't think we need to worry about cyborgs becoming common. Some internal electronics would be useful, such as hearts that wouldn't wear out. However, there is a great deal science doesn't yet understand about the interactions between the body and the brain. Until more is known, removing healthy biological parts would at best be risky.

A point not often considered is that there may be an evolutionary reason for the limitations of our natural brains. For example, it has been suggested that our senses could be improved to the extent of seeing light within more frequencies; after all, many animals can see infrared or ultraviolet light. But they cannot see both, or even as many colors as we do. Dogs can hear higher frequencies than humans and have a far stronger sense of smell, but they have a shorter range of sight. It has often been said that humans have an adaptive advantage over other species because we are generalists--we are able to adapt to many environments instead of being limited by specialized characteristics that contribute to survival under specific conditions. The price we paid for this ability may have been, in part, the loss of sensory inputs associated with specialization. To sense too much of the world at once might be so overwhelming that we could not focus on the information relevant to our immediate needs.

We have a still greater adaptive advantage because of our cognitive ability. And too much input data might be even more detrimental to this ability than extended sensory input. Information overload is already a major problem for many people who find it hard to get anything done when exposed to constant bombardment by data from television and the Internet. Unless it could be selectively turned off, an ongoing neural connection to the Net would make this situation much worse. It has been theorized that the reason extrasensory perception (ESP) is rare may be that the brain acts as a filter to keep out the flood of information that would otherwise engulf it. Whether or not this is true, the same principle may apply to conventional input. To be deluged by too much might lead to mental prostration if not to insanity.

Neuroscientists are attempting to "read" thoughts from brain waves or technologically facilitate transfer of thoughts from one person to another, or to a device.

Some scientists are experimenting with a sort of technological "telepathy" involving exchange of information directly between brains via the electrical signals associated with types of thought. They also plan to expand the concept of mentally activating electronic devices that it's now hoped will benefit disabled people. However, it's questionable how practical this would be for wider use. Some say we'll be able to control all our household appliances mentally, yet would that not be a distraction from whatever more significant things we were thinking about? Intellectual activity depends on concentration; to clutter minds with tasks best left to external devices would be a backward step.

As to the increasingly-common notion that it will become possible to upload minds to machines and do away with bodies entirely, it is a fallacy I have discussed in several other essays. Here it's not relevant, since if it were possible for a human mind to exist in such a state we would have to revise our entire conception of personhood, and that would nullify everything previously believed about being human.

*

All the above speculations are based on an assumption that Earth in the future will be very much the same as it is today. Of course, we can't be sure that there won't be a disaster such a nuclear war, a pandemic caused by bioterrorism, or any of a number of other catastrophes suggested by dystopian science fiction. Such scenarios can be ruled out as far as making predictions about the future is concerned, since the effects would be so overwhelming that no prediction would be meaningful. But it's possible that lesser world-altering events may occur.

It's all too likely that there will continue to be non-nuclear wars, at least for the foreseeable future. (Hopefully not forever--see my essay "Humankind‘s Future in the Cosmos.") AI will have a major impact on warfare, although the U.S. military is opposed to using weapons that can operate without human control and many AI researchers believe they should be banned. Various AI devices to aid human soldiers are under development, however, and surely AI will fill many non-combat military roles. I suspect that no ban on autonomous weapons could last because eventually, despite treaties, some rogue nation or terrorist group will deploy them. Of greater concern than actual military conflict is the extent to which cheap AI devices, such as tiny drones that target specific people, could be used against civilians by terrorists or even for murder. The same technology used for legitimate devices could also be used for destructive ones, so it's hard to see how they could be kept out of the hands of criminals.

There are other potential calamities. Many people today think that if we don't lower our standard of living, climate change will ruin our planet’s environment. (An expanded version of this section now appears in my ebook From This Green Earth under the title “The Only Sensible Way to Deal with Climate Change.”) In my opinion this particular fear is greatly exaggerated. Contrary to the widely promoted theory that climate change is due to human activity, some scientists believe it is entirely, or almost entirely, the result of natural processes. The idea that we are responsible for it is popular because it offers false hope that we can stop or reverse it, and because it provides an opportunity to vent feelings about it by placing blame.

That said, it would be wise to reduce pollution of the atmosphere whether the climate changes significantly or not. And it is indeed getting warmer, which may cause a rise in sea level and frequent droughts, among other effects. We can no more prevent this than we can prevent earthquakes. We may someday be able to control the weather in specific locations on a short-term basis, but the only solution to problems with the climate is to develop technologies for adapting to it, as humans have been doing since we first built shelters and learned to use fire. That is how evolution works; when environmental changes occur, a species adapts or it dies out. Through extragenetic evolution, we can choose to adapt before our survival is endangered.

NASA's Landsat satellites continuously monitor the condition of Earth's land, forests, agriculture, and oceans.

By the time climate change is sufficient to threaten the well-being of people in industrialized nations, the changes in lifestyle made possible by AI will have begun, and the use of AI will lessen its impact. People are going to be moving away from cities, and climate change will accelerate the process. This does not mean that no one will become homeless, but that situation will have to be dealt with anyway, merely from the upheaval accompanying the introduction of AI. Moreover, AI will lead to major improvements in agriculture and food distribution that will mitigate the effects of drought.

However, the problems that will be caused by global warming will be much greater in Africa and Asia than they will be in America. At worst, a rise in sea level could force Americans to move out of waterfront cities and abandon beach homes, but in Asia large populations live in low-lying coastal areas and would have nowhere to go. Developing nations do not have the technology for dealing with high temperatures, such as air conditioning, that are already common in industrialized ones. Nor do their traditional methods of agriculture and food storage provide much leeway in case of extreme weather.

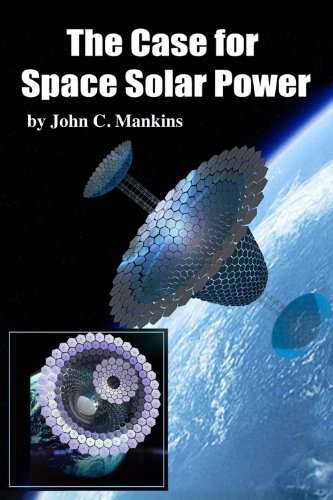

So one of the best ways of adapting to climate change would be to help the people of developing nations obtain modern technology and AI devices. But how could they afford them and the infrastructure required to make them work? I see only one solution, and it's something we should have begun long ago for the welfare of everyone in the world. We need to develop space-based solar power (SBSP).

The key to raising living standards in developing nations is power. About 3 billion people, mostly in Africa and southern Asia, have no access to electricity. They must use firewood, which they often spend hours gathering, for cooking and heating, and smoke-induced diseases are responsible for the death of 4.3 million people every year. Use of electronic devices is out of the question for these people, but more than that, they need power merely to gain utilities standard in the rest of the world. Yet industrialized nations rely mainly on oil and coal for generation of power, which is a major source of pollution and which will not last indefinitely. It can't be made available worldwide, nor can renewable sources such as Earth-based solar power meet the need.

Since the 1970s it has been known that solar power could be collected by satellites in space and beamed to Earth--to all parts of Earth. This would not only provide plenty of relatively inexpensive power to the nations that launched the satellites, but could raise the rest of the world out of poverty. It would enable the people of poor countries to adopt a lifestyle appropriate to the twenty-first century. Many experts have studied proposals for such a system, but it has generally been considered too expensive a project to undertake. A few, notably the late Gerard O'Neill, have pointed out that it would not be too expensive if materials obtained from the moon were used for construction of space stations in order to save the cost of lifting them out of Earth's gravity well. However, since the moon has been neglected for the past half-century, we will have to develop SBSP without the benefit of lunar resources.

Solar power from space would reduce energy costs, lift developing nations out of poverty, and end pollution of Earth's environment by the use of fossil fuels.

This is the only option that makes sense. And it will provide more than power--it will make much-needed water accessible, too. Drinking water is not easy to get in rural areas of developing nations; in Sub-Saharan Africa 14 million women and over 3 million children spend more than 30 minutes a day carrying water for their households, often from ponds or streams. Water may become scarce in America, too, if climate change adds to the need for irrigation of crops. Already some cities, such as Los Angeles, depend on piping water from distant rivers; if those rivers dried up or an earthquake cracked the pipes, millions of people would die of thirst. And population growth in itself is threatening the water supply. Sooner or later it will be necessary to desalinate seawater. So far, that has been too costly; but with cheap space-based solar power it could be done.

Power satellites will also make possible the utilization of extraterrestrial resources by private industry. Entrepreneurs like those now building spaceships will mine materials from the moon and asteroids and use the profits to expand their operations in space. Eventually, through the use of AI, manufacturing will be done in space as well, and industry that pollutes will be moved out of the atmosphere into orbit where it belongs. This process could restore Earth to its natural beauty, though that won't occur until far in the future.

The large-scale use of power and/or materials from space will be the first major step in extragenetic evolution since our prehistoric ancestors began using metal. It will mark the transition of humankind from a planet-bound species to a spacefaring one, a transition that is essential to the long-term survival of our species. If climate change proves to be the spur needed to make it happen, then like many other apparent misfortunes in our history, that may someday be seen as a blessing.

I have said more about spacefaring in my essay "Humankind's Future in the Cosmos" and in my book From This Green Earth: Essays on Looking Outward. It is unquestionably part of the future of being human, if humans continue to thrive. But I don't think colonizing other worlds will alter the lives of ordinary people more than moving to unfamiliar environments has in the past. From generation to generation, we will go on as we always have, forming relationships, loving each other, giving birth to children, raising families--and wondering about the mysteries of the universe that remain beyond our grasp.

*

To sum up, I believe the future won't be as different from today as most speculators think. Much that is written about it nowadays is biased in favor of the views of people who are so excited, or so appalled, by speculation about upcoming technology that they fail to think about what being human means to them. Underneath, we all know what it is to be human. Why should we assume that our descendants will be unlike ourselves?

People will go on as they always have, loving each other, starting families, looking toward the future with hope.

To be sure, the rapid progress in the field of neurotechnology is disconcerting, for though brain implants are a blessing to the disabled and perhaps someday to victims of dementia, more complex ones, if used by normal people, might alter their personalities--or even lead to the probing and/or influencing of their thoughts by the government. Yet I suspect that in the end, that wouldn't affect our humanity. When it comes right down to it, either human minds are more than brains, or they are not. If they're not, then it does not really matter how brain implants affect them because we never were what we thought we were to begin with; there is nothing to be lost. But if there is more to us, as I am convinced that there is, then no form of technology can take it away.

"I don't believe these interventions change who a person is, who they fundamentally perceive themselves to be," says neurologist and bioethicist Judy Illes, director of the Neuroethics Canada center at the University of British Columbia. "They may change many features around identity, but I believe that the self is resilient to the intervention." I'm sure that she is right. The human self is a mystery, and perhaps the failure of brain enhancement to suppress it will shed light on its true nature.

And perhaps it will also serve to reveal the nature of psi powers. The one truly life-changing event to come in the future will be society's acknowledgment that such powers--telepathy, clairvoyance, and psychokinesis--exist. The scientific proof that they do can't be ignored forever. A time will come when enough people in responsible positions accept them to turn the tide. The military is actively researching practical applications of psi, and it may be that as in so many other areas of science, military-funded developments will lead the way to civilian use. However, psi normally works entirely on an unconscious level. Public acceptance won't mean that the average person will become consciously telepathic. Widespread use of psi won't occur until the distant future, and will be a major step in human evolution. It will not alter humans in any essential way, but unlike technological progress, it will have a significant impact on personal lives and relationships as well as on human culture as a whole. The result, I believe, will be greater harmony among people everywhere.

I have been told by friends that the world is declining. To them it seems that way, in part because of political issues and in part because of technological changes on the horizon which they think will somehow dehumanize society. To judge from Google search results they are far from alone. Yet every generation has felt that way. Disapproval of the government and predictions of doomsday have never been lacking, and inventions from the printing press to electric lights have been deplored for their alleged threat to human values. In 1900 a Portsmouth, NH reporter wrote, "Now comes the electric telephone, which offers promise. It promises, detractors fear, to strike at the very sociability of our community. People who would normally seek out each other's company may now speak over a wire." This is just what's now being said about children using cell phones. In the future it may be said about neural connections to the Internet. Plus ça change. . . .

In 1829 Thomas Carlyle, one of the most important social commentators of his time, wrote a long essay titled "Signs of the Times." In it he declared, "Were we required to characterise this age of ours by any single epithet, we should be tempted to call it . . . above all others, the Mechanical Age. It is the Age of Machinery, in every outward and inward sense of that word. . . . Our old modes of exertion are all discredited, and thrown aside. On every hand, the living artisan is driven from his workshop, to make room for a speedier, inanimate one. The shuttle drops from the fingers of the weaver, and falls into iron fingers that ply it faster. . . . There is no end to machinery. Even the horse is stripped of his harness, and finds a fleet fire-horse [train] invoked in his stead. Nay, we have an artist that hatches chickens by steam; the very brood-hen is to be superseded! For all earthly, and for some unearthly purposes, we have machines. . . ."

Carlyle believed that not only physical mechanism but what he considered mechanism of social, political, and intellectual pursuits were signs of declining humanity. He asserted, "Men are grown mechanical in head and in heart, as well as in hand." Nevertheless he was optimistic: "Mechanism is not always to be our hard taskmaster, but one day to be our pliant, all-ministering servant. . . . That great outward changes are in progress can be doubtful to no one. The time is sick and out of joint. . . . The thinking minds of all nations call for change. There is a deep-lying struggle in the whole fabric of society; a boundless grinding collision of the New with the Old. . . ."

I think this is applicable to our own time. People deplore what is new because it is so noticeable that they lose sight of the fundamental things that endure. There is no need to worry about artificial intelligence surpassing us. Future technology and the freedom from routine work it provides will offer more opportunity to do things that are uniquely human, not less. Opportunity to be, or communicate, with friends and loved ones; to enjoy nature or sports; to ponder and create. If AI can do everything else that once only humans could do, so much the better. That will free us to simply be human.

Being human is an inner quality not dependent on outer form or overt activity. It cannot be lost or diminished as long as we are alive. That will remain true, no matter how many things change in the world of tomorrow.

Copyright 2020 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.

This essay is included in my ebook The Future of Being Human and Other Essays