The End of Personal Privacy

by Sylvia Engdahl

The widespread use of artificial intelligence (AI) will bring an end to personal privacy as we have known it—not only will government surveillance be expanded, but people will be all too willing to accept implanted devices for shopping convenience and health monitoring. Furthermore, “brain-reading” technology poses a growing threat.*

In addition to the many conveniences artificial intelligence will offer us, it will have effects that are less desirable. Like all technology AI is a tool, but it will be a powerful tool in the hands not only of consumers and industry but of government. Right now, despite increasing surveillance of citizens, government use of the data is limited by the fact that far more is being collected than it is possible to analyze. AI excels at analysis. We are going to have very little privacy in the future, and if the wrong kind of government gets into power, we are not going to have much freedom from interference in our lives.

AI will undoubtedly lead to extensive recording and examination of information about ordinary individuals and their activities. Although the secret mass collection of phone records from all customers of America’s large phone companies was banned by Congress in 2015, by obtaining records of those contacted by the contacts of persons targeted for investigation the government is still gathering data about a great many people who are not suspected of any wrongdoing. The legal controversies about such practices won’t be resolved soon, and probably won’t put an end to them.

Collection of phone records is the least of the tactics already being employed for surveillance, even in democratic nations. Thousands of closed-circuit TV cameras, some with facial-recognition capability, watch the streets of London and New York. The U.S. border is patrolled by drones and towers that detect individuals’ movements and a zeppelin that can track cars and boats within 200 miles of the Florida Keys, while DNA is collected from everyone in immigration detention. “The deployment of invasive technologies may be done in the name of border security,” says a report at gen.medium.com, “but they’ll likely find their way deep inside the United States. Almost every technology developed at the border in the last two decades now exists in the armories of local police departments.”

These measures pale, however, beside the intrusion on individual privacy that will be made possible by implanted devices. Implanted microchips are already in use on a voluntary basis; while they can’t yet track location, that capability will soon be added, and they may not remain voluntary. Some types of surveillance will be unavoidable in view of the increased danger from AI-equipped criminals and terrorists, and hopefully, safeguards will exist to prevent misuse of the data collected on innocent citizens. But the government’s definition of “misuse” is unlikely to match that of privacy advocates.

When I wrote Stewards of the Flame in 2005, I made up the whole idea of the implanted tracking chips. It seemed to me a likely distant-future development, considering that we were microchipping cats and dogs. I wasn’t aware until later that passive chips were already being implanted in humans and that there were many blogs and articles on the Web opposing them. One of the earliest objections was Christian fundamentalists’ claim that such chips are the “Mark of the Beast” referred to in the Bible (considered by scholars to be a metaphorical reference to the oppressive rule of Rome). The comparison is rather more apt than was evident at the time, considering that the mark was said to be required “so that no one can buy or sell” unless he has it, for this may well prove to be the main reason for the acceptance of implants by the public.

Implanted microchips are increasingly being used for opening locks, paying for items, and logging onto computers as well as for ID.

Already thousands of people in Sweden are using implanted chips in place of cash and credit cards, and employers here are beginning to offer them to workers for use at the snack bar as well as for ID purposes. Their potential for such use is limited mainly by the lack of scanners in stores, a problem widespread installation of AI will eliminate. The convenience of not having to carry money or ID is undeniable—some people have chips merely to avoid having to carry door keys. In time credit cards, which can be lost or stolen, will no longer be issued. And the advantage to vendors in not having to hire clerks and safeguard money is so great that once microchipping is widespread, they may be unwilling to accept cash. In Stewards I portrayed implants as entirely bad, the immediate cause of my protagonists’ decision to escape to a new world—and then only a few years later in Defender of the Flame, without thinking twice I had my hero use his to pay for a sandwich. Eventually this is how all shopping will be done.

By the time implantable tracking chips become available, they may seem no more objectionable than GPS-equipped cell phones. Even before then, however, AI could easily track someone by a trail of purchases; to conceal one’s movements one would have to refrain from buying even a cup of coffee. In the more distant future, it’s probable that the chips will be able to pick up sound, meaning that room-bugging technology will be obsolete and no conversation anywhere can be considered private. AI may analyze all conversations in real time on the chance of preventing a crime; that’s the sort of task to which it’s well-suited. And implanted chips will be as active inside homes as elsewhere, unless the public demands the provision of a way to turn them on and off.

Like cell phones and the Internet, implanted microchips will have a major effect both on society as a whole and on people’s daily lives. Future generations of children will wonder how their forebears managed without them. Hopefully some sort of protection against unwarranted invasions of privacy will be established. but even if it is, there will be criminals, if not agencies, that break the rules—that chips will be hacked is virtually certain. All technological advances (and for that matter, sociological ones) have both good and bad consequences, and we could not escape the latter even if we chose to forgo the former; that’s an inherent aspect of human progress. We can only hope that the worst-case scenario—the possibility that implanted chips might be made compulsory and used for controlling the entire population—will never become a reality.

*

If the prospect of losing our privacy to tracking chips is dismaying, that of subjecting the inner status of our bodies to surveillance is even more so. Yet surprisingly little concern about this issue can be found on the Web. Though the mere implantation of identifying microchips has been viewed with alarm for many years, the prospect of other types of body sensors, even implanted ones, seems not to have aroused much worry. Perhaps no one has noticed the scary implications of what is happening to healthcare. On the other hand, perhaps the magic word “health” has blinded people to the possibility that the price of pursuing it to extremes might turn out to the loss of their autonomy. Stewards of the Flame was intended as a warning, not a prophecy; but I’ve begun to wonder whether it’s less far-fetched than I realized while writing it. Probably the least credible premise in the novel is that in a time when we have starships, implanted health monitors won’t be used just as much on Earth as in a colony that carries medical surveillance to excess.

At the time I was writing the book I had no idea of the extent to which remote health monitoring was already being developed, or that monitors now merely wearable will be implantable very soon. They are by no means limited to heart monitoring—among the many experimental skin and under-skin devices that now exist are sensors for glucose, blood pressure, stomach and lung performance, and the presence of cancer. Microchips are only the beginning; in 2016 it was announced that engineers at UC Berkeley have created experimental dust-sized, wireless sensors that can be implanted in the body, bringing closer the day when a wearable device could monitor internal nerves, muscles or organs in real time.

As if ongoing observation of one’s bodily functioning weren’t enough, there’s even research underway on a tooth patch that can track what a person eats. Furthermore, as the Washington Post reported in 2018, “Bluetooth-equipped electronic pills are being developed to monitor the inner workings of your body, but they could eventually broadcast what you’ve eaten or whether you’ve taken drugs.”

If even the contents of your toilet bowl can be accessed by health providers (and/or government health promoters) via the Internet, the very concept of privacy will be endangered.

A number of companies are now developing “smart” toilets that sample urine and feces, measure body fat, and check blood pressure, heart beat, and/or weight when a person sits down. “The experience of using such a toilet won’t be intrusive,” says Sam Gambhir, director of the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection. “People will simply go to the bathroom, flush and go on about their day. Meanwhile, the toilet will analyze the user’s waste, identify the person using fingerprint sensors embedded in the flush handle and then send the results to the cloud or an app on a smartphone.” This is not intrusive? Such a statement goes to show how insensitive people have already become to the crossing of lines once considered inviolable.

As of 2018, three million patients worldwide are currently connected to a remote monitoring device that sends personal medical data to their healthcare provider. Remote monitoring has become big business— most of the many websites now devoted to it are produced by suppliers of equipment and software. They discuss advantages and disadvantages from the standpoint of medical providers, emphasizing their needs and what they feel patients want, or should want. In looking at these sites, one must bear in mind that their aim is commercial. Still, they reveal the handwriting on the wall as to what the future may hold. When monitoring is done by AI the expansion of the concepts now being introduced (plus many more under development) will be virtually unlimited.

There are many legitimate uses for remote health monitoring. In addition to its value in providing continuous data about chronic medical conditions, it’s invaluable for people who live in remote locations, or are too ill to visit medical offices easily, or lack transportation—in fact, it may eventually be less costly than office visits even for people physically able to make them. It’s certainly less time-consuming. And enabling the elderly to stay in their own homes instead of nursing homes is an indisputably desirable goal.

However, as a 2014 article in Health Affairs points out, “Sensors that are located in a patient’s home or that interface with the patient’s body to detect safety issues or medical emergencies may inadvertently collect sensitive information about household activities. For instance, home sensors intended to detect falls may also transmit information such as interactions with a spouse or religious activity, or indicate when no one is home.” Though the aim of such devices may be simply to protect health, their potential uses won’t stop there; and they may pave the way for data collection with less beneficent purposes. Either corporate or government interests could easily be served by secret incorporation of undocumented capabilities.

Those are not the only troubling questions raised by increasing availability of monitoring technology. People with chronic illnesses will welcome it. But once a person chooses to be monitored for a specific medical problem, where does it end? I don’t want well-meaning healthcare professionals checking up on my body’s condition and how I live my life. Most of the discussion about privacy in connection with medical technology centers on whether the data can be made secure against unauthorized dissemination. But I want privacy from medical providers, too, except with respect to problems for which I’ve intentionally sought help. The right to keep one’s own body private is recognized in all other contexts. If one’s bodily status and even the content of one’s toilet become subject to daily examination by “authorities,” the very concept of personal privacy will inevitably be weakened.

This issue is particularly serious in the case of very old, or very ill, people who prefer to die naturally rather than on life support in a hospital. In the novel Jesse remarks that such people often refrain from doing anything about terminal illness: “That’s how my great-granddad went, and nobody questioned it, and what he didn’t tell the doctors was left unsaid.” But if such people are monitored earlier when they do want treatment, will there be any way to stop? Or will the ambulance automatically come for them, just as in the story? As far back as 2001 an article in EE Times stated, “‘We’d like to believe that someday a pacemaker could send a signal directly to a satellite. . . . When it comes to this kind of patient management, we’d like to believe the sky’s the limit.”

Already the market is flooded with wearable fitness monitors. Is it good for people to be constantly aware if their internal functions, let alone make this personal data available for electronic surveillance by others?

Moreover, it’s likely that once remote monitoring of illness becomes common, people who are healthy will want to be monitored just in case some illness should develop later. And that trend will be fueled by the suppliers of monitoring equipment, who like the pharmaceutical companies will do their best to convince medical providers, employers, and the general public that health depends on the use of their products. In a 2018 issue of Huff Post Jessica Baron writes, “The implications of anyone else knowing your fitness level, heart rate, nutrition choices and step count range from humiliation to outright discrimination,” yet even now some employers and insurance companies are urging workers to wear fitness monitors in exchange for rewards. At least one has tried, so far unsuccessfully, to make it compulsory. If this idea catches on, insurance may eventually be denied to people who refuse to submit to monitoring,

The scary thing is not so much the possibility that someday an arbitrarily-imposed law might require implanted microchips, but that the public will come to favor such a law for healthcare reasons if not out of concern for national security. It’s all too easy to imagine the voters deciding that everyone ought to be monitored “for their own good,” just as they’ve passed laws forcing everyone to wear seatbelts.

In many countries it wouldn’t even need the concurrence of the voters—where the government pays for all medical care it would be viewed as cost-saving measure. Although at present the common idea that “preventative care” saves money is not true—the cost of unnecessary testing and treatment of the people who would never get seriously sick exceeds that of caring for those who do—internal monitoring might more accurately determine who is truly at risk. Wouldn’t it be a good thing, then, to identify and treat these people whether or not they want to be treated? I don’t think so. Apart from the fact that there are many reasons why a person might not wish to know about future illness, in my opinion there is no justification for depriving an individual of free choice for any reason other than protecting others from direct harm. And that includes the choice to be free of unwanted physical surveillance.

But this freedom may not withstand the pressure of our society’s dedication to health as the highest good and the pursuit of it as a moral, rather than mere practical, obligation. (See my essay “The Worship of Medical Authority.”) “It’s only a matter of time before the exam-room-centered focus of patient care gives way to management of assigned populations to maintain or improve health,” wrote John Morrissey in the July 8, 2014 issue of Medical Economics. And once people get used to medical monitoring will they not be less adverse to the thought of the government making use of implanted devices for whatever purposes it finds convenient? It looks as if my longtime conviction that medical “benefits” are a foot in the door for tyranny may not be far off base.

*

It might seem that ongoing monitoring of people’s internal bodily status is the ultimate invasion of privacy. But neuroscientists are predicting an even more disturbing one. They say that brain-sensing technology will enable the reading of people’s thoughts.

The media, reporting on the activities of high-profile research organizations and entrepreneurs, have presented such a possibility as “mind-reading technology” and “technological telepathy” (though it is more accurately called “brain-reading”) and have quite rightly expressed alarm. Ethicists in many countries are considering what to do about protecting neural privacy. “The potential for governments to make us more compliant, for employers to force us to work harder, or for companies to make us want more of their products underlines just how seriously we should take this technology,” says Garfield Benjamin in a recent article in The Conversation.

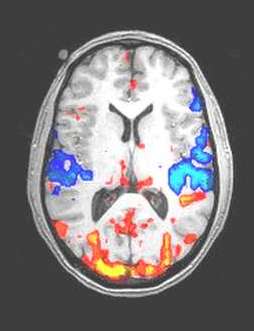

Brain scans obtained by fMRI are presently used for medical purposes and for lie detection, but in the future they may be able to show more about a person's thoughts.

Most research so far has involved non-invasive technologies such as brain scanning via fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging). It is already being used for lie detection. The principle by which this works is that if a subject is lying the effort will cause activity in certain areas of the brain, which will result in increased blood flow to those areas that is visible on the scan. But it is not always accurate, since other types of mental effort involve the same areas of the brain. And a recent study has found that people can trick the test by using mental countermeasures.

More advanced research with fMRI has shown that it is possible to determine from brain scanning what a subject is looking at, at least in terms of similarity to stored images. Even more than that, “If I threw [you] into an MRI. machine right now . . . I can tell what words you’re about to say, what images are in your head. I can tell you what music you’re thinking of,” medical imaging firm Openwater’s founder Mary Lou Jepsenis told CNBC in 2017. Perhaps in time brain scanning will enable recording and identification of a person’s memories of what he or she has seen in the past, or even dreamed. Since fMRI now requires the subject to cooperate by lying still in the tunnel of a large machine, it is not likely to be practical for police interrogations—but that may not always be true. Jansen says she has put “the functionality of an MRI machine . . . into a wearable in the form of a ski hat.”

“The right to keep one’s thoughts locked up in their brain is amongst the most fundamental rights of being human.” Paul Root Wolpe, director of the Center for Ethics at Emory University in Atlanta, told CBS News in a 2009 episode of “60 Minutes.” Yet the law at present doesn’t say who will be allowed to scan people’s brains. It’s important, he said, to decide “whether we’re going to let the state do it or whether we’re going to let me do it. I have two teenage daughters. I come home one day and my car is dented and both of them say they didn’t do it. Am I going to be allowed to drag them off to the local brain imaging lie detection company and get them put in a scanner?”

Even more difficult is the question of whether to permit surreptitious scanning of people who aren’t suspected of anything. fMRI scanning is already being used to try to figure out what we want to buy and how to sell it to us. Product designers and advertisers use brain scanning and other techniques of the rapidly expanding field of neuromarketing to determine the most effective ways of appealing to customers. So far this is done with volunteer test subjects in laboratories, and unlike some commentators, I see nothing wrong in using the information obtained to induce the public to buy. But if the technology advances to the point of scanning the brains of customers who aren’t aware they’re being scanned, that is something else entirely—as is the issue of scanning innocent people’s brains to determine whether they’re likely to commit crimes in the future.

Whether technology can ever do anything approaching transmission of actual thoughts remains to be seen. Already, however, it can detect emotional states. In China many workers in factories, public transport, state-owned companies and the military wear caps with built-in EEG (electroencephalogram) capability that scan their brainwaves and send the data to computers that use AI to uncover depression, anxiety, rage, or fatigue. At first there was resistance because they thought (mistakenly) that the caps could read their minds, but they soon got used to them because they look just like safety helmets. An advanced version is being developed by hospitals to monitor patients’ emotions and prevent violent incidents.

Research on more invasive technology such as brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) is presently focused on unquestionably-beneficial medical uses. Even now, it is possible for a paralyzed person to control a computer cursor or even a robotic arm by thought alone, But Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, has more ambitious hopes. His company Neuralink is developing strands smaller than a human hair that can be injected into the brain to detect the activity of neurons. Though presently intended for medical purposes such as helping quadriplegics and people with Parkinson’s disease, the technology, according to Musk, will eventually enable humans to be interfaced with superior AI, which in his opinion will otherwise leave us behind.

Today’s BCIs generally require brain surgery, which can be justified only for people with serious illnesses who can benefit from it. But that will change. In 2017 a company called Neurable demonstrated a virtual reality game using a headstrap that enabled a player to move, pick up objects, and stop lasers entirely by thought. The U.S. government’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) is funding development of thought-sensing hardware that will be embedded into a baseball cap or headset and will be bi-directional, able to transmit information back to the brain in a form that the brain will understand.

Many types of direct detection of brain signals are being developed and more advanced ones are envisioned. If the content of people's brains can't be kept private, there will be no such thing as privacy.

Facebook is funding similar research. In collaboration with researchers at the University of California at San Francisco it’s now working on an implanted BCI that converts brain signals to words and could help patients with neurological damage speak again by analyzing their brain activity in real time. But eventually, it hopes to produce a non-invasive wearable device designed to let users type by simply thinking words, control music, or interact in virtual reality. “It’s also bound to raise plenty of questions concerning privacy,” an article at Futurism.com points out. “Our thoughts are one of the last safe havens that have yet to be exploited by data hoarding big tech companies.” Since Facebook has lost the trust of many users due to past privacy violations, its involvement may cause the device to be met with suspicion.

All of the above projects involve communication between brains and machines, but technology-assisted brain-to-brain communication is also possible. In 2013 researchers at Duke University enabled rats to communicate through their implants, resulting in the “receiver” rat pressing the correct lever without being able to see the signal given to the “sender” rat. At Harvard, humans with non-invasive EEG BCIs were able to mentally control the movement of a rat’s tail. In 2019 Chinese scientists enabled rats to move through a maze when guided by a wireless connection to a human brain. Neuroscientists believe it may someday be possible to communicate with animals, including our dogs and cats, by brain-sensing and thus learn what they are thinking (although if this requires putting implants in their brains I doubt that many of us will choose to do it).

Experimental brain-to- brain communication between humans has been achieved, too. A single-word message in the form of encoded and decoded binary symbols has been successfully sent brain-to-brain from a person in India to one in France. Images have been projected from one mind to another. And the University of Washington has developed a game called BrainNet, a much-simplified version of the video game Tetris, in which shapes on a computer screen are moved by the thoughts of players in separate rooms wearing brain caps.

There are many exaggerated claims being made about the dangers of our alleged coming ability to send messages by brain-sensing “telepathy” or scan the Internet through mind alone, allowing hackers—or governments—to gather personal information, from our political opinions and sexual preferences to our ATM pin numbers. However, most of these scenarios are based on misunderstanding of the technology. As physicist Michio Kaku points out in his book The Future of the Mind, privacy issues may not be as great a concern as the public thinks, since neural signals degrade so rapidly outside the brain that they cannot be understood by anyone more than a few feet away. Thoughts used to access the Internet could reach only as far as a personal computer or smartphone, which would convert them to words and transmit messages or commands via ordinary wi-fi. And in the unlikely event that a way were found to detect brain signals from a distance, noise signals from outside would block them.

Nevertheless, it would be possible for hackers, or the manufacturer, to install spyware on personal computers and smartphones that would decode more brain signals than the user has authorized—so the potential for privacy violation does indeed exist unless adequate security precautions are taken. And the need for proximity to the brain is no barrier to the use of neural sensing to get information from people detained by authorities or enemies, nor could it protect them from revelation of any anti-government thoughts they wish to conceal. “To me the brain is the one safe place for freedom of thought, of fantasies, and for dissent,” Duke University professor Nita Farahany told MIT Technology Review. “We’re getting close to crossing the final frontier of privacy in the absence of any protections whatsoever.”

Personally, I view neurotechnology with mixed feelings. On one hand, it is of immense benefit to disabled people. Furthermore, it may shed light on the extent to which thought is entirely the product of brain activity, as distinguished from the unknown mechanism that materialists refuse to acknowledge—it may even help us learn to consciously control our natural psi capabilities. (Neurofeedback was, after all, the method used in the Flame novels, written before I knew such technology actually existed.) On the other hand, the all-too-real prospect of government and/or criminal abuse of brain-reading technology is indisputably frightening.

Copyright 2020 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.

This essay is included in my ebook The Future of Being Human and Other Essays