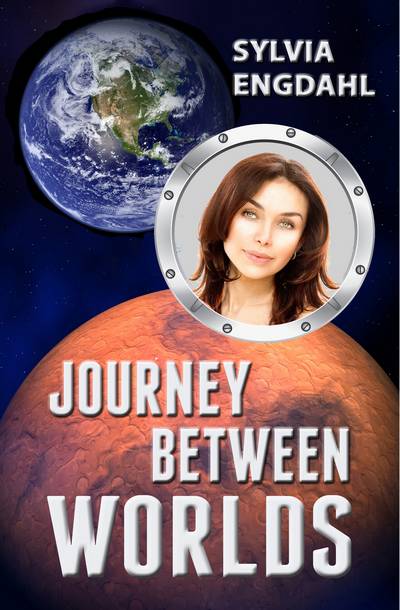

Excerpt from

Journey Between Worlds

A young adult science fiction romance

by Sylvia Engdahl

I never wanted to go to Mars. So many girls plan to be flight

attendants, or ship's technicians, or if they're going to get a degree,

they hope to land a position in the Colonies just as soon as they can

qualify; and not only because of the fabulous salaries. I was never like

that. In our senior year, we used to talk about college and jobs, and

all the things we wanted to do with our lives--though of course we knew

that for most of us, Europe or Africa or maybe Tahiti would be the

extent of our travels. Even then, what I wanted was to live in a house

overlooking the bay, with the sparkling blue water in front and dark

trees behind, near the town where my mother's folks had always lived.

And since teaching was a career that would let me do that, I did not

intend to let anything stand in the way of getting my Oregon teaching

credentials as soon as I possibly could.

Yet here I am in New Terra. There are times when I still can't believe it.

Sometimes I dream about the water lapping on the rocks below Gran's beach house. Or the sand, white instead of red and damp where the tide has left it, and the breeze smelling of salt and seaweed and free oxygen. And the firs, ragged green against a pale blue sky, and white clouds billowing up behind the mountains . . . or fog. Fog, soft and wet against my face, and indoors, the comforting fragrance of a crackling wood fire.

Then when I wake up and first remember how far away those things are,

I don't see how I can bear it. And I lie there thinking about all that's

happened, and wondering whether making a trip to Mars was very foolish

of me or very mature. You can't ever plan everything out in advance, I

guess. But I used to think I could. I don't think I wanted too much;

the trouble was, I didn't want enough. . . .

I was disappointed not to get even a glimpse of the Susie from the outside, but we never were outside; outside was vacuum. I had seen pictures and knew that she was huge, and shaped rather like a dumbbell, with the power plant in one sphere and the passenger decks in the other. But all I saw when I went aboard was a perfectly ordinary passageway with doors opening off at the sides and some steps going off at unbelievable angles. The Susie's flight attendants, who wore red uniforms instead of blue, came to meet us and escort us to our staterooms. We wouldn't be allowed to walk around by ourselves until the ship broke contact with the shuttle and got her spin back.

That was where I was separated from Alex and also from Dad. I already knew that I'd be sharing my stateroom, for there's no room to spare on a spaceship and all the cabins are double. I wasn't prepared for just how small it would be, though. (If you've ever seen one of those "sleeping cars" they have in railroad museums, you've got the general idea.) There was barely room to stand up next to the double-deck bunk. And of course, no window. When the flight attendant closed the door behind him, I thought for a minute I was going to get claustrophobia after all, especially since that door wouldn't open again. Then I saw the sign on it: THIS EXIT IS AUTOMATICALLY SEALED DURING MANEUVERS AND ZERO-GRAVITY. IN CASE OF EMERGENCY RING FOR THE ATTENDANT. I spotted the bright red "panic button" and felt a little better.

The cabin lights were dim, and my roommate was lying on the lower bunk with a blanket pulled up over her and the safety net loosely fastened; all I could see of her was the back of a blonde head with short, tousled curls. She didn't move when I came in, or even when there was a knock and another flight attendant appeared with my duffel bag. I wondered if she was sick until I remembered that by ship's time it was nearly midnight.

I didn't want to go to sleep. I wanted to go out and find Dad. I wanted him to hug me tight and call me "Mel, honey" in that comfortable, affectionate way of his that I was coming to depend on, and maybe tell me once again just why it was that we were in this cramped, chilly cocoon of a ship on our way to Mars. But there was no way to do that, so without bothering to undress I clambered onto the upper bunk--which wasn't really up, of course--and buried my face in my arms.

Eventually I did fall asleep because I was worn out. Sometime later,

about the time that would have been dawn if there were any dawn in space,

we sailed. I never knew it. It was a low-g maneuver; I didn't wake to

feel the weight seeping back into me as the Susan Constant

slowly eased into her outbound orbit, toward another world.

Copyright 1970, 2006 by Sylvia Louise Engdahl