Plus 50 Years and Counting

by Sylvia Engdahl

April, 2019: When I put this page online seven years ago, its title referred to the time since the first human flights into space. Now it has been fifty years since the more signficant steps of the first flight to another world and, a few months from now, the first landing. Once, like most space advocates, I would have approached this milestone with a feeling of dismay and frustration that we have not used that half-century to go further into space, as in 1969 we expected would happen. I would have viewed it as a failure of humankind to live up to our potential, a loss of the initiative and boldness in the face of challenge that has characterized our species in the past. As shown in the comments below and elsewhere at this website, I have gradually come to see it differently. I no longer think that more rapid progress in space was to be expected--and I no longer feel that it was needed. We are on track!There was never any realistic chance of getting widespread public support for the space effort in our era, nor was such support necessary. All past human advance has been achieved not by public support but by individuals or small groups whose vision was not widely shared and who achieved what they did not to benefit the public but to fulfill personal goals, make a financial profit, or gain a better life for themelves and their families. It is no different now--we didn't make significant advance toward becoming a spacefaring civilization until private entrepreneurs started building spacecraft and putting them to practical use. My recognition--described here and elsewhere--that the majority of humans view space with underlying trepidation is not a cause for pessimism. On the contrary, it suggests that the past 50 years of apparently-stalled progress were not a tragio waste of time.

As the anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing appraches, I will be writing more formally and at greater length about this, as I think it's something disillusioned space enthusiasts need to consider.

Space advocates know and love this song, "Hope Eyrie," written by Leslie Fish and performed by Julia Ecklar. When I discovered that it's available on YouTube I was eager to add it to my website, as it expresses the deep feeling many of us have about the Apollo moon landing:

The Eagle has landed,

Tell your children when.

Time wonít drive us down to dust again.

June, 2012: The Space Age began more than half a century ago in the spring of 1961, when Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space and Alan Shepard the first American. Less than nine years later, in 1969, its promise was spectacularly fulfilled when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon. The event was hailed then as the giant leap for humankind that it was; but as space advocates know all too well, despite some valuable achievements of the space shuttle, progress in terms of extending our presence in the universe has been stalled. Only a few weeks ago, I would have titled this page "Plus Fifty Years and Holding," and while the successful mission of the SpaceX Dragon to the International Space Station has made me hope that forward steps will now resume, my renewed optimism may be premature.

June, 2012: The Space Age began more than half a century ago in the spring of 1961, when Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space and Alan Shepard the first American. Less than nine years later, in 1969, its promise was spectacularly fulfilled when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon. The event was hailed then as the giant leap for humankind that it was; but as space advocates know all too well, despite some valuable achievements of the space shuttle, progress in terms of extending our presence in the universe has been stalled. Only a few weeks ago, I would have titled this page "Plus Fifty Years and Holding," and while the successful mission of the SpaceX Dragon to the International Space Station has made me hope that forward steps will now resume, my renewed optimism may be premature.

And yet, there is another reason why I am not as discouraged as I have been these past few decades. Recently, while revising my 1974 nonfiction book The Planet-Girded Suns for republication, I was struck by the parallel between our era and the emotional reaction prevalent in the early 17th century among people who were realizing that the universe was much larger, and less neatly arranged, than had previously been supposed. I had expressed similar ideas in my 2006 essay Achieving Human Commitment to Space Colonization: Is Fear the Answer? But I had not noticed the historical comparison, or perceived that the long hiatus in space exploration is not only natural, but unavoidable--should in fact have been predictable to those of us knowledgeable about the history of ideas--and that like all stages of human evolution, it is of limited duration.

To quote from my 2012 Afterword to Planet-Girded Suns, "Possibly I see now what I did not see earlier only because I am past the age of hoping that I will live to watch humans travel beyond the moon (or even that far, unless a privately-funded expedition gets there). Yet to me it is reassuring to realize that, barring some major disaster to Earthís civilization, the present unwillingness to accept the challenge of space will pass. That it is not a aberrant prolongation of the Critical Stage as I have long feared, but simply a pause to prepare humankind for the momentous journey ahead."

In any case, I believe this alternate view of our slow progress is worth considering. The Afterword, titled "Confronting the Universe in the Twenty-First Century," also appeared in The Space Review, but the version here at this site includes the 2016 update.

*

July, 2016: I have just republished Planet-Girded Suns with a different subtitle, and in doing so I added the following update to the Afterword.

Reading this essay four years after its publication, I feel more than ever that what I have said explains the reluctance of the public to support a major effect toward human expansion into space. The danger in confining our species to a single planet despite the possibility of worldwide disaster is too obvious for me to doubt that there are deep-seated psychological reasons for the publicís refusal take it seriously. Perhaps, in addition to the factors I have already mentioned, people do not want to think to think this danger is real, and are therefore unwilling to acknowledge it by accepting the need for an offworld presence. And yet a great deal is said about threats to Earth, and the majority of the people most concerned about them are the ones least apt to push for space colonization. So underneath, suppressed fear of the vast unknown universe must be stronger than worry about asteroid strikes, nuclear war, excessive climate change, or runaway biotechnology.

But now, there is greater cause for optimism about progress in space than there was four years ago. Now, privately-owned ships are delivering supplies to the space station, manned flights are soon to follow, and a privately-funded mission to Mars is in the planning stages. This is the first truly promising development since the Apollo era. I have always known that private investment alone could bring about a real breakthrough, but I feared that investors would not grasp the enormous economic potential of space activity and extraterrestrial resources until far in the future. Iím thankful that it has proved to be a mistaken fear.

And so I feel sure that we are on track, and that the gradual extension of our speciesí range will occur just as it always has, through the efforts of individuals who take risks for the sake of what they personally believe, or hope to gain, and thereby bring about gain for all humankind. That is how it has worked in the pastówith the earliest tribes that ventured beyond their territory, with the explorers who sailed from Europe to the New World, and with the later pioneers who migrated to the American West. It is not necessary for society as a whole to support such efforts. Had widespread enthusiasm been needed for Columbus to sail, he would never have left Spain. It is only looking back that we see the full value of what individuals strive to do, and this will be as true of progress in space as it has been on our home world.

A colony on Mars may not be established in my lifetime, but I am confident that it will be during the lives of most people who are now living. Whether they like the idea or not does not matter, any more than public opinion mattered at the time Bruno first suggested that there are planets circling other suns. Ultimately we will reach some of those exoplanets, and long before we do, spacefaring will seem as natural and desirable as air travel does today. In the light of human history, we need not be discouraged by the fact that the time is not yet ripe for this outlook to prevail.

Below are some past comments that aren't long enough to warrant pages of their own. For a long time I haven't written much about space; one grows weary of saying the same things, most of which have been widely discussed on the Web by other space advocates, over and over again to readers that remain unconvinced. And as I say above, I no longer think it is either possible or necessary to convince the general public. But I have never lost my belief--which I have held for well over sixty years--that it is vital for us to become a truly space-faring species before it's too late to save Earth, and ourselves, from eventual ruin.

October, 2007: (Posted in the blog I had at that time, which is still online but no longer maintained.) I'm a couple of days late in commenting on the 50th anniversary of Sputnik. To my own dismay I've realized I was too busy to think about it, although the historical significance of humankind's first venture into space cannot, in my opinion, be overestimated--and as I've said often before, the launch of Sputnik struck me at the time as providential. I'd then believed for quite a while (and still believe, despite the long hiatus) that putting human energy toward the effort of getting into space is the only way of averting a catastrophic global war. I suppose I overlooked the date this week because after more than 50 years of focusing on the importance of space, I have become disillusioned by our lack of progress toward establishment of a permanent presence on other worlds. But in a way I am glad that I didn't post about the anniversary sooner, for I now have the opportunity to comment on the excellent op-ed by Charles Krauthammer in today's Washington Post (also syndicated elsewhere, including my local newspaper).

"We had no idea how lucky we were with Sputnik," Krauthammer says, and goes on to point out that it led not only to Apollo and the moon, but to other major technological advances such as ARPANET, which became the Internet, and to the establishment of the principle that orbital space is not national territory. But the main point of his op-ed is something less widely recognized, something that I myself fully grasped only a year ago, and commented upon in an article at my website [Achieving Human Commitment to Space Colonization: Is Fear the Answer?] which is now also included among the reports at the Lifeboat Foundation's website. The public's lack of willingness to proceed with space exploration is not mere apathy. It is fear, I suggested, "that has been holding the majority back, not conscious fear, but the stirring of an unconscious recognition that the universe is very much vaster, and more scary, than most people like to think."

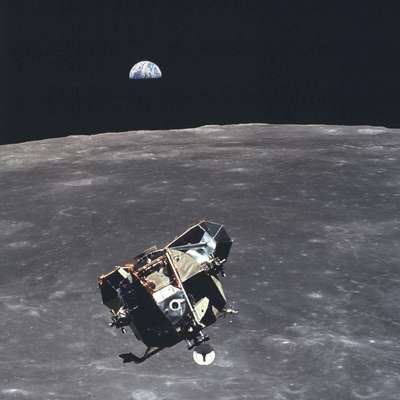

Before Sputnik, Krauthammer points out, "We always assumed that one step would create the hunger for the next--ever outward from Earth orbit to the moon to Mars and beyond. Not so. It took only 12 years to go from Sputnik to the moon, which we jumped about on for a brief interlude and then, amazingly, abandoned. There are technological, budgetary and political reasons to explain this. But the most profound is psychological." Those of us with enthusiam for space and a longing to see humankind venture further have been slow to realize this, as for us, the attitude predominant in our society is hard to understand. And yet Krauthammer is right when he says that the famous photo "Earthrise" did not just spur the environmental movement. "With surpassing irony," he observes, "it created at the very dawn of the space age a longing not for space but for home."

"This is perhaps to be expected for a 200,000-year-old race of beings leaving its crib for the first time," he declares. And it is, of course. It's surprising, I guess, that we did not expect it, and have interpreted it as a discouraging sign that humankind may be doomed to eventual extinction through dependence on the limited resources of a single world. To accept the thought of long delay isn't easy for those of us who are no longer young enough to see society's outlook change within our own lifetime. Yet I hope and believe that Krauthammer is also right when he concludes, "We will, however, outgrow that fear. It was 115 years from Columbus to the Jamestown colony. It will take about that same span of time for a new generation--ours is too bound to Earth--to go out and not look back."

February, 2003: Right now, we are all mourning the tragic loss of the space shuttle Columbia. My feelings about the possible public reaction are the same as those expressed in my 1986 commentary on the Challenger tragedy, which have been online at this site since 2001. I also agree with the fine article "Why We Must Still Go Boldly" by Seth Shostak, posted February 3 at www.space.com [once archived elsewhere, but unfortunately no longer online]. However, I think that Shostak does not go far enough. He rightly points out that the pursuit of scientific knowledge, though essential, is not the only justification for human exploration, and that what we most remember and admire about the Lewis and Clark expedition is "not the volume of their data, but the triumph of their journey." This is true, but do we not remember Lewis and Clark still more because they paved the way for the opening of the vast Northwest Territory to settlement? (Perhaps this is obvious to me because I live in Oregon, where it is a key point in regional history.) Do we not remember Columbus more because he found a new continent to be settled than in connection with exploration for its own sake?

For many years it has troubled me that even ardent advocates of space exploration generally state that its prime purpose is to seek scientific knowledge--that in fact, not only is its funding sought on this basis, but in virtually all categorizations of subject matter, "Space" is listed under "Science" as if that were its sole significance. This strikes me as comparable to listing Lewis and Clark under "Science" because of the data they collected about flora and fauna, or to listing everything related to computers under "Science" (which once seemed reasonable) because they are indispensable to scientists.

I am a strong supporter of scientific research. I do not question the need to pursue it in space or in any way doubt the immense value of the knowledge that can be gained there about the universe. But as Shostak points out, this "often fails to resonate with the public." And that is hardly surprising, since it is no real answer to the questions of those concerned about immediate problems such as starvation, disease and imminent war. Yes, scientific advance will help to alleviate these problems in the future; and yes, the fundamental human urge to explore is in itself of value to our well-being and must not be discounted. But why rely on these arguments when there are far stronger ones for maintaining a human presence in space? Why not recognize the scientific knowledge to be gained from the space program as the byproduct it is, and start educating the public about why moving beyond our home planet is vital to the survival of future generations?

If you have not read my essay Space and Human Survival, please do so now!