From the Journal of an Alien Observer

by Sylvia Engdahl

I wrote this essay nearly fifty years ago, in 1970, with the naive hope that I might get it published somewhere—this was, of course, long before the Web existed, and there were still magazines looking for articles. Naturally this hope came to nothing; apart from the experimental format of the essay, it was far too controversial. Then as now, any criticism of the environmentalist agenda was doomed to obscurity. At that time Zero Population Growth (ZPG) was a major political movement; today other goals are more prominent. What they all have in common is the belief that the long-term problems of our planet can be solved while remaining confined to it, which in my opinion is a dangerous misconception.

*

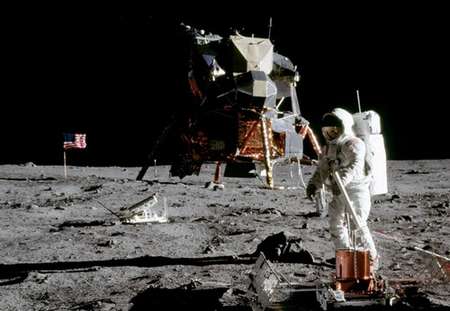

The planet spun in space, spun as it had been spinning for countless millennia, a blue and lustrous sphere that revealed nothing of the race that had evolved upon it. That was how we saw it as we approached, when for the first time its inhabitants too were viewing it in true perspective—three of them from a vantage point reached at awesome cost in money, in effort, and in risk; the majority from the comfort of their homes by a means that seemed incongruously commonplace. Some of these people watched in near-disbelief, some in pride, some in joyful thanksgiving; but others shook their heads, convinced that the view had been achieved through a mistaken sense of priorities on the part of a race never prone to let itself be guided by reason. And later, when the leader of one of the planet’s most powerful nations characterized the initial landing on a neighboring globe as the greatest event since the Creation, many of his hearers doubted that assertion. For one reason or another, they felt that a people so beset by difficulties and despair had more pressing needs than to set footprints in the dust of a lifeless world.

Among the doubters, to be sure, were some who did see one justification for the accomplishment. It had symbolic value. It was eloquent proof that what humans set their minds to, they could do; moreover it demonstrated once and for all that their world was a single entity, that its divisions had less cosmic significance than had hitherto been supposed, and above all that whatever affected any part of that world must inevitably affect the whole. “There it is,” they said, “and it is all there is. We had better be careful of it, for there is nowhere else to go.”

Those who spoke so thought themselves very far-sighted, and they indeed showed more foresight than their ancestors—more, in fact, than most of their contemporaries. They were among the supporters of their era’s newest cause: the cause of environmentalism. The human race had had many causes, but this one was worthier than most and more mature. Its adherents felt that at last, in the nick of time, a lesson had been learned about the perils of failure to look ahead. They had perceived a danger to their planet and were aware that only positive action could avert it.

They were right. But they did not look far enough ahead.

That they did not is understandable. The danger was real and frightening, and it overshadowed abstract theories about the destiny of humankind; if it was not circumvented humankind seemed unlikely to have any destiny. Old values were crumbling, and was not the ancient injunction, “Be fruitful and multiply,” both outmoded and damaging? The propensity of humans to multiply had become a curse. A time was approaching when the planet’s finite resources could not support any more people. The fact that this truth had itself been abstract theory until comparatively recently in no way lessened its import.

A determined few had always maintained that the natural resources of the world must be conserved; now these prophets’ fanaticism was being vindicated. The cause was gathering momentum. It was becoming identified with the once narrowly-defined issue of human survival. That issue had been a matter of grave concern ever since technology had progressed to the point where inadvertent self-destruction was a distinct possibility for humankind, but the threat had been thought limited to full-scale war. People had learned to live with it. They denounced the folly of such war and dedicated themselves to the pursuit of peace. Then, in horror, they saw that even if lasting peace was achieved long-term survival would remain open to question. The human race was likely to destroy itself anyway through pollution of its environment. This realization was enough to scare all but the most complacent; it was small wonder that the traditional ideals, which were already losing their hold over society, had begun to collapse with ever-increasing rapidity.

So as the inhabitants of the planet Earth saw their world from space through the eyes of the first men to leave it, a number of them declared the project wasteful and irrelevant. “We have the technology to control our environment and thus to ensure survival,” they argued. “It is that upon which our effort must be expended. Collecting moon rocks may be an amusing pastime; space exploration might even lead to a new renaissance of the human spirit as its advocates like to claim; but in this age of crisis it is a luxury we cannot afford.”

As with reasonable people of any era, their logic was flawless; it was their premises that fell short. First, the premise that environmental control could ensure human survival indefinitely; and second, the premise that the first tentative venture into a new environment—a venture to which humanity had committed itself despite all the more obvious demands of this particular moment in history—was a luxury, an irrelevance, or for that matter even a chance undertaking.

It is the lot of humans to be misled by false premises; this is unavoidable, for the premises of one era are necessarily naive in the next, and the new era’s innovators are too busy demolishing those of the past to examine the ultimate implications of their own. They do not possess enough data for a full examination in any case. That is why reason alone can never produce progress—why planning, however conscientiously undertaken, can never provide the assurance that humankind will prevail. Fortunately, it is characteristic of human beings to resist detailed planning. Humans are perversely unreasonable, a trait that may have more survival value than it appears to in the light of any given set of assumptions.

This is not to say that planning for the future is not needed; on the contrary, such planning is vital, and becomes progressively more so as a world’s civilization enters the phase where the planet itself is endangered. But plans must not be based solely on current knowledge; they must take future breakthroughs into account. Although it is impossible to foresee the precise nature of these breakthroughs, it is realistic to suppose that they will occur. Furthermore, it is not too difficult to picture what would happen if they did not occur—and if the future thus pictured leads to a dead end, it is safer to allow for more hopeful contingencies than to be satisfied with making the best of a seemingly-unalterable situation.

The premises held by the people of Earth in the year following their first landing on another world led to a very dead end indeed, but to most this was not apparent. The ultimate implications of those premises had not been given much consideration. To consider them was a terrifying thing for a culture so lacking in faith as was Earth’s at that period; there were terrors enough that were immediate and unconcealable, and the idea of a dilemma for which no scientifically-endorsed solution could be discerned was not to be borne. Most had, after all, placed what small faith they possessed in science, having forgotten that science by definition concerns only that portion of truth which no longer demands faith for acceptance.

What was the dilemma implicit in the premises of those who were pinning their hopes on environmentalism? It proceeded from their central tenet:

Earth has too many people, and unless something is done it will eventually have more than it can support. That, of course, was no mere premise, but a demonstrable fact. The trouble lay in the assumption that was drawn from it: The thing to do is to achieve zero population growth. That, and only that, can save humankind.

It was natural enough for that assumption to seem incontrovertible. Zero population growth sounds like a wise goal and indeed, as an immediate, short-term one, it is. For a planet at Earth’s stage of development it is an essential stopgap measure. But its long-range implications are less encouraging. To work toward it is beneficial; to maintain it indefinitely means the end of human advancement—followed, inevitably, by the downfall of the human race. It cannot save a world’s people; it can only buy time.

The whole question of zero population growth is perhaps academic; quite possibly natural law, which transcends humankind’s limited wisdom, prevents a static population level from being attained on any world. If it were to be attained, however, the results would be far from salutary. To begin with, its cost would be disastrously high: not the material cost—for any sum could be counted well-spent in the cause of racial survival—but the cost in human terms. Almost certainly, zero population growth could never be achieved by purely voluntary means. A sharp drop in the birth rate, yes; but a birth rate that did not exceed the death rate would necessarily involve some form of compulsion. Many would feel that survival at the price of basic personal freedoms would be no victory for humanity, but would instead constitute a tragic and self-defeating dehumanization of the species.

Others, to be sure, would disagree. Loss of the individual’s freedom to have children would not seem too high a price to those who believe that individual rights should be subordinated to the good of society as a whole. Yet there remains a less easily-dismissed issue: that of society’s freedom to have children. Though the loss of this freedom was not imminent for the planet Earth, it could scarcely be denied that if medical science continued to make strides toward increasing life expectancy the problem would someday arise. The advocates of permanent population stabilization did not deny it; they had simply not visualized a world where no one could have a child until somebody agreed to commit suicide.

“No one” is an exaggeration, of course; some people would die in accidents and others, ultimately, of old age—but not often enough to allow each generation to reproduce itself. Child-bearing permits would be few. Who would get them? The healthiest? The most intelligent? Those judged by the current psychological theories to be the most competent parents? Those nominated in the wills of the decedents? Those most sympathetic to the government in power? Since none of these criteria could be considered compatible with the concept of equal rights under the law, it might be preferable to have a lottery.

Or perhaps nothing of the sort would be necessary. Perhaps a point would be reached at which life expectancy could be increased no further, by which time there would be so few people of child-bearing age that births and deaths would automatically fall into balance. Perhaps medical research would be deliberately curtailed; or, alternatively, the universal right to produce offspring would be retained on condition that anyone who exercised it would suffer the death penalty at some predetermined age. There might be more children than one would think under such a system; the desire for descendants is potent, and a society in which it was almost totally frustrated would not be a happy society.

It would not, in fact, be a viable society. Since the beginning of time viable societies have been expanding ones, and there has invariably been correlation between the rate of expansion and the advances made by civilization. The people of Earth were well aware of this until acceleration of the rate, with its attendant problems, led them to suspect that their once-firm belief in the desirability of growth might be a myth. It was not a myth, though the problems were nonetheless painful and perplexing for that. No culture can remain static; it must always be changing and growing—or else declining. If the mere stoppage of population increase did not produce such a decline, the lack of young blood surely would. It is the young through whom advances come. Disquieting as a new generation’s excesses may be to its parents, in their hearts the elders know that a world without youth would be a world without hope.

Hence the dilemma: on the one hand, it had become evident that Earth’s people could not survive on an overpopulated planet; on the other, it was equally certain—although less widely recognized—that total stabilization of the population would lead to stagnation and eventual decadence of the human race. Either alternative would, in the end, mean humanity’s extinction.

But there was a third possibility: that of continuous expansion through colonization of other worlds.

Very few people took this possibility seriously. It was forgotten that very few had taken travel to the moon seriously until they had seen live telecasts from space, and that still fewer had recognized overpopulation as a serious threat prior to the emergence of environmentalism as a popular cause. It was hardly surprising, in view of humankind’s traditional lack of foresight, that the priority of the space program was being judged on the basis of immediate benefits—or lack of them—rather than of significance for the distant future. It was unfortunate, however. It was particularly unfortunate that the men and women who were most aware of the dangers inherent in failure to plan ahead were among the ones most likely to advocate cutback of space exploration; yet a poll commissioned by a prominent conservationist group, the National Wildlife Federation, indicated that 44% of those interviewed favored diversion of funds from the space program to environmental cleanup.

That money had to be found for environmental cleanup was indisputable, but those who felt it should be taken from the space program were defeating their own real purpose. They were overlooking the crux of the issue: there would come a time when no more cleanup was possible, and by that time the people of Earth must be ready to move on.

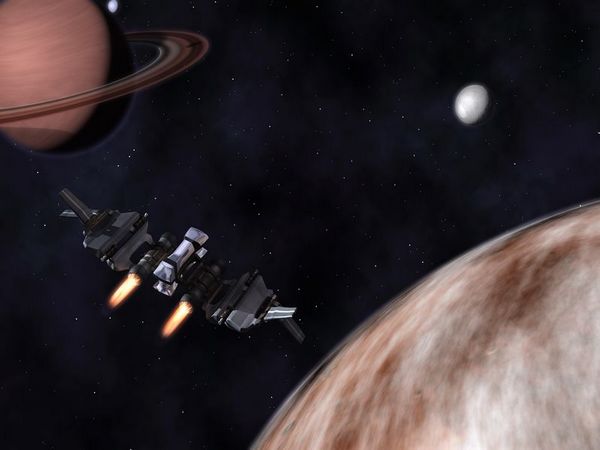

Move where? It was a legitimate protest, for close viewing of the moon and of Mars had only confirmed the belief that those worlds were inhospitable. Venus was still less promising, and the remaining planets of the solar system were wholly unsuitable for terrestrial forms of life. Lunar and Martian colonies could be established, given another fifty years or so of technological advancement; but they would be limited in size for they would be dependent on atmosphere-enclosing domes. They could not begin to solve Earth’s population problem. Their cost, which would be tremendous, could not be justified on that basis.

Nevertheless, an all-out effort toward colonization of the local solar system was justifiable. Such effort is always justifiable as a necessary step in a human race’s progress toward its true goal: the stars.

“Progress” was an unfashionable concept on Earth at the time of the initial space ventures. Most enlightened observers no longer believed in it. The continued presence of evil and injustice in the world seemed to blind these observers, accustomed as they were to the accelerating pace of change in their own era, to the fact that worse evils had been outgrown and that even the poverty-stricken were leading far more comfortable lives than their counterparts twenty, ten, or even two centuries back. The people of the day rarely took a long view; both in their private lives and in their judgment of society, they wanted quick results. It was suggested that the young had been conditioned to this attitude by continuous exposure to current merchandising methods. Perhaps; but in any case their elders were no less bound by it, and such an outlook does not foster an understanding of human evolution, which like personal maturation is a slow process that invariably involves pain.

The people of Earth had no proof that evolution would take them to the stars; even the most ardent believers could do no more than recognize that there was no other place for it to take them. Their only surety lay in the realization that they could not stand still and survive. Yet this realization alone provided sufficient grounds on which to gamble, for it was clear warning that if the hope of interstellar expansion proved false, then someday their race would die.

There were formidable obstacles. Interstellar colonization was not feasible in terms of their era’s scientific knowledge. Although it had been estimated that the universe might contain several billion solar systems with planets capable of supporting life, few of them were within range of the fastest ships conceivable under current hypotheses. The velocity of light was, according to the principles of relativity, the maximum speed that could ever be attained; and this limitation was a matter not of technology, but of basic theory. It would require a totally unpredictable breakthrough to circumvent it. Furthermore, development of a means of propulsion that could enable spacecraft to approach the speed of light was far beyond the capabilities of existing technology and would remain so for a long time to come.

Assuming that such a means of propulsion would eventually be found, various possibilities had been discussed in contemporary literature. Voyages of centuries’ duration could be undertaken if the passengers were kept in suspended animation, or if huge arks, ecologically balanced, were designed to support successive generations that would live and die aboard before the destination was reached. Better still, if ships could travel at a high enough percentage of the speed of light for the relativistic time-dilation to have significant effect, interstellar voyages would consume comparatively few years of subjective time although centuries could pass on Earth while the travelers remained young. None of these schemes, however, were practical in the expansive sense. They might serve to transport small groups of human beings to worlds where new and independent outposts could be established, but communication with the mother planet would be precluded by the time lapses involved. Like the intra-system colonies, such outposts would be worthwhile experiments—perhaps vital ones—yet they would offer little potential for large-scale extension of terrestrial culture; moreover their status would not be known soon enough to be of any help as far as the overpopulation of Earth was concerned.

It was necessary, therefore, to face an alarming truth: humankind’s ultimate fate hinged on the unpredictable breakthrough, the breakthrough that would permit two-way traffic between the stars.

No one could predict the timing of such a breakthrough. No one could foretell its character. But one thing was certain: if and when it occurred, humans must be prepared to take advantage of it. Technology that can colonize a hundred worlds, a thousand worlds, is not achieved overnight; its development is gradual and must proceed step by step through a long period of trial and error. During that period environmental pollution, even when slowed by sane controls, looms as an ever-greater threat. If the conquest of space is delayed until most of a world’s people can see the true basis of the need, it is too late. There is simply not enough time left for the required head start.

On the planet Earth few understood the nature and urgency of the need; yet nevertheless, space was being conquered. It was being conquered for all sorts of reasons that had nothing to do with human viability centuries or millennia hence. National pride had a part in the enterprise; so did fear of the military advantage that space supremacy might give to an enemy. The innate desire for adventure and challenge played a large role. The courage of the astronauts was inspiring in an age that lacked heroes; the skill of those who were proving that the moon was within reach afforded a rare opportunity for optimism; science welcomed the unprecedented chance to gain knowledge of the universe. Technological advances achieved through space research had obvious benefits in that many of those advances could be applied to the improvement of conditions at home—a fact upon which the program’s supporters found it necessary to place heavy emphasis, although a small minority did realize that space exploration could provide an outlet for energy that might someday replace war, and that in any case an undertaking of such magnitude could not fail to initiate far-reaching cultural innovations.

Some of these motives were decidedly naive, as their critics lost no opportunity to point out, and others, although valid in themselves, were indeed of debatable priority; only the least comprehensible were wholly sound. Was it mere chance that criticism, including much legitimate criticism, went unheeded while expedition after costly expedition pushed outward into space? Or was it a case of evolutionary laws overriding the limited knowledge of the time? People frequently do the right things for the wrong reasons. Those of Earth had acted in defiance of logic before, often to their ultimate benefit; perhaps it is always so in a species’ painful struggle toward maturity.

Perhaps it is so even in regard to the despair-provoking horrors of that struggle: it is not inconceivable, for instance, that the problems of peoples confined to their mother worlds—the poverty; the explosive population pressure—and above all, the wars that sensible people think futile and preventable, yet somehow fail to prevent—are all essential spurs, stimuli through which society, being unable to plan rationally for a future it cannot envision, is given motives compatible with its level of advancement and is thereby forced to take the steps necessary to ensure that future. Perhaps the inexplicable anguish of the human condition is not as purposeless as it seems.

Be that as it may, for Earth’s inhabitants the central issue was not what they thought it to be when, disturbed by the expense and the risk of the drama that was unfolding on their television screens, they questioned the value of manned space probes. They were rightfully concerned about preserving a livable world for their descendants. But in the long run, those descendants’ lives would depend upon their ability to leave not only their home world but also their solar system. Such ability could not be developed in a decade nor yet in a century. The effort could not wait until the need for it was apparent, as the need for population and pollution control had become apparent. If there was anything to be learned from the current environmental crisis, it was that shortsightedness in setting priorities can be tragically costly. It would be the height of irony if humankind’s response to one failure of foresight should lead to another, less reparable, failure: if in their zeal to rectify the abuse of their native environment, humans should neglect to prepare for their emergence into the universe wherein their sole salvation lies.

Environmentalism is a vital cause, yes—without it, a world’s civilization cannot last long enough to reach the stars. But as we of races older than Earth’s have long known, it is only a means to an end. We can only hope that the people of this planet will realize that before it’s too late to begin moving beyond.

Copyright 2019 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.