The Once and Future Dream

by Sylvia Engdahl

This is the only new essay in the 2024 revised edition of From This Green Earth. While I have expressed some of these ideas before, it highlights one that I now feel is of particular importance: the impact of the first sight of Earth from Apollo 8. Although it took awhile for the reaction to set in, I believe this, rather than Apollo 11, was the turning point, the day on which, for the second time in history, the public's conception of the universe was forever changed.

*

Once upon a time, more than half a century ago, a dream that had inspired people for over three hundred years reached the first milestone toward its fulfillment. Only an exceptional few had shared it at first, and it had taken a very different form, a form that persisted throughout most of its history as more and more of the educated public became fascinated by the idea. Its modern form emerged in the late nineteenth century. At that time some people began to believe that in the future it might really become possible to travel in space.

The longing to do so, and especially to reach the stars, affected many people from the time they become aware that stars are other suns surrounded by planets. But this was far from the initial reaction to that fact, which had not been even suspected until the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno suggested it in late sixteenth century.

This was pure intuition on Bruno's part, and because he was not a scientist he has not been given the credit such an innovative concept warrants, at least not in English-speaking countries. It was contrary to the science of his time; even Copernicus, whom he admired, had believed that the stars were mere lights firmly fixed to relatively nearby celestial spheres. It was also contrary to the teaching of the Church, and as a result Bruno was burned at the stake in 1600. Although he was also guilty of other heresies, this was probably the one that caused his inquisitors to imprison him for eight years hoping to make him recant. No doubt they sensed its truth and found it frightening, as did most who heard of it before the late seventeenth century.

.People of the early 17th century were upset by the idea of stars scattered in space without any apparent order in the universe.

Bruno's books were banned, which in itself attracted followers who were excited by them. As the idea spread among more conventional scholars, however, it was extremely upsetting, The thought of stars as huge, fiery spheres at random distances from Earth dismayed people who had believed that the universe was orderly and unchanging, and who had previously associated eternal fire with hell. Moreover, the movement of the planets in our solar system was predictable and had been precisely calculated, which could not be done with stars now conceived as loose in space, As the poet John Donne expressed it, "New philosophy puts all in doubt" and Earth is lost among the stars, "all coherence gone, all just supply and all relation." The philosopher Blaise Pascal's famous statement, "The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me," may have been the typical reaction of his contemporaries. A universe that isn't neatly arranged and run like clockwork does not feel safe.

It took a long time for this feeling to die out. Nevertheless, the new cosmology took hold as scientific support for it grew, beginning in 1610 when Galileo published an account of his observations of the sky through a telescope. These showed that contrary to previous belief, heavenly bodies are not perfect, unblemished spheres; worlds other than Earth exist, if not other suns. Later a theory of Rene Descartes about fluid vortices carrying them through space overcame objections based on traditional physics, which held that there could be no such thing as a vacuum. These developments led the way for the very first suggestions of future space travel and even of space colonization.

In a letter written to Galileo in 1610 astronomer Johannes Kepler wrote. "As soon as somebody demonstrates the art of flying, settlers from our species of man will not be lacking. . . . Given ships or sails adapted to the breezes of heaven, there will be those who will not shrink from even that vast expanse." It is unlikely that anyone else saw this private letter, but in 1638 John Wilkins, a bishop of the Church of England, published a long and very influential book about the moon in which he declared, "It is possible for some of our posterity to find out a conveyance to this other world, and if there be inhabitants there, to have commerce with them."

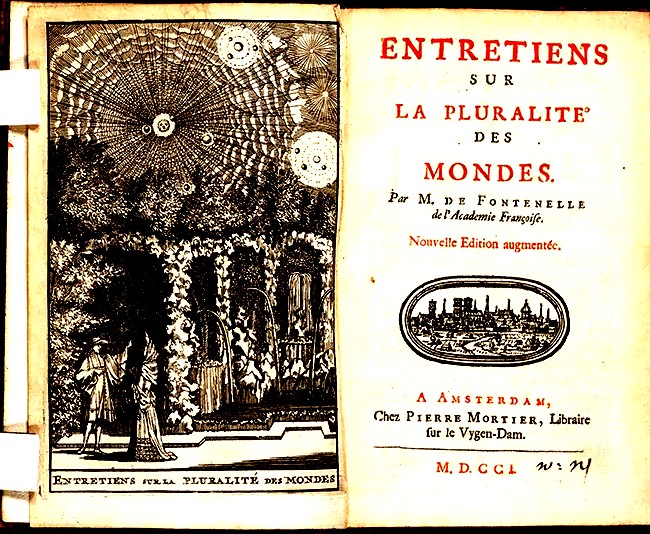

There is no evidence that this was taken seriously by his readers, for no similar comments followed. Although stories about voyages to the moon appeared during the next two centuries, they were meant as pure fantasy. Interest in actually seeing other worlds took another path entirely. But first, the public learned of the existence of multiple suns with planets through the first popular book about them intended for laymen rather than scholars, Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds by French author Bernard de Fontenelle. It became a bestseller, perhaps because unlike all other science books of that time it was specifically directed to women. Fashionable ladies were entranced by it, and it forever transformed the idea of multiple worlds from a dreadful thought to a fascinating one.

Fontenelle's bestselling book Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds took the form of a philosopher and a countess discussing astronomy while strolling in her garden.

Two major developments firmly established the new cosmology as the standard view of the universe by which few people were disturbed. First, an assumption about other worlds' purpose, emphasized by Bishop Wilkins and considered conclusive for the next two and a half centuries, caused religious authorities to stop opposing the idea of other worlds and become its most ardent defenders. Virtually everyone agreed that God could not have created a world without any purpose. Therefore it must be of use to someone, and since distant planets were of no use to Earth (a presumption today's space colonization advocates might question) it must have inhabitants of one kind or another. A picture emerged of countless inhabited worlds, attesting to the power and glory of God.

The other major factor in the triumph of the new cosmology was Isaac Newton's discovery of gravitation. Initially the idea of gravity was rejected by science because it was seen as an "occult" force, much as conventional scientists of today view ESP. All authorities insisted that nothing short of divine intervention could act at a distance. But Newton's mathematical laws of planetary motion explained things that could not be explained in any other way. Moreover, they restored confidence that there is order in the universe--people no longer had to face the frightening thought of planets drifting without any pattern. So gradually the Newtonian system prevailed.

By this time educated people who read current books and magazines had heard a lot about the new astronomy and most were eager to know more. There was much speculation about other planets' inhabitants, who were almost always assumed to be superior to humankind. Some thought they were angels, while others viewed them as mortals without the flaws all too evident in natives of Earth. A great deal of poetry, some of it book-length, presented detailed descriptions of spectacularly beautiful suns and their attendant worlds. Often it took the form of space voyages, not science fiction but imaginary journeys presented as having ocurre4 during a dream or with a spirit guide.

Enthusiasts found it very frustrating to think that they could never really see distant regions of space--that as far as anyone knew, no humans ever could. And so some began to dream of the future, not posterity's future but their own. Though it was impossible for mortals to travel in space, they thought they might do it after death on their way to Heaven.

A British clergyman, William Derham, wrote a very popular book titled Astro-Theology. It was mostly about astronomy, but at the end of it he said, "We are naturally pleased with new things; we take great pains, undergo dangerous voyages, to view other countries: with great delight we hear of new discoveries in the Heavens, and view those glorious bodies with great pleasure thro' our glasses. With what pleasure then shall happy departed souls survey the most distant regions of the universe, and view all those glorious globes thereof, and their noble appendages with a nearer view?"

Though this was not the doctrine of any church, it was not incompatible with existing concepts of an afterlife and many clergymen espoused it. The idea caught on, or perhaps was intuitively felt by people who simply couldn't bear the thought of never seeing more of the universe than was visible from Earth. Richard Gambol's long poem Beauties of the Universe sums it up, telling of a time when the soul

Unbounded in its ken, from prison free

Will clearly view what here we darkly see:

Those planetary worlds, and thousands more,

Now veil'd from human sight, it shall explore.

Shortly after the death of Newton, who was revered as the greatest scientist who had ever lived, there were many such poems; people couldn't believe that so great a man wouldn't have a chance to see the worlds whose motion he had explained. As one woman put it, "With faculties enlarg'd, he's gone to prove / The laws and motions of yon worlds above; / And the vast circuits of th'expanse survey, / View solar systems in the Milky Way."

David Mallet's The Excursion: a Poem in Two Books devotes many pages to what Newton's soul perceives:

When Isaac Newon died much poetry appeared desribing his sight of the stars and their planets close up on his way to Heaven.

Ten thousand worlds blaze forth; each with his train

Of peopled worlds. . . But how shall mortal wing/p>

Attempt this blue profundity of Heaven,

Unfathomable, endless of extent!

Where unknown suns to unknown systems rise,

Whose numbers who shall tell? stupendous host!

Sun beyond sun, and world to world unseen,

Measureless distance, unconceiv'd by thought!

. . . What search shall find

Their times and seasons! their appointed laws,

Peculiar! their inhabitants of life,

And of intelligence . , , each resembling each,

Yet all diverse! . . .

About me on each hand new wonders rise

In long succession.

In prose, too, descriptions of souls' travel to the stars appeared during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In a popular book published in 1840 Thomas Dick wrote, "The law of gravitation . . . separates man from his kindred spirits in other planets, and interposes an impassable barrier to his excursions to distant regions, and to his correspondence with other orders of intellectual beings. But in the present state he is only in the infancy of his being. . . He will, doubtless, be brought into contact and correspondence with numerous orders of kindred beings, with whom he may be permitted to associate on terms of equality and of endearing friendship. . . It may be necessary that branches of he universal family that have existed in different periods of duration, and in regions widely separated from each other, should be brought into mutual association, that they may communicate to each other the results of their knowledge and experience." That looks like an astonishingly modern prophecy until seen in context, which shows it to refer to the afterlife. People's hopes and aspirations don't change; they merely take the form appropriate to the era culture in which they are expressed.

Today's readers are apt to dismiss these writings as merely religious, without relevance to the growth in human understanding of the actual universe. But there was no firm line between religion and science in that era. Only more recently were they separated by more than the availability of data to analyze; the word "scientist" was not coined until 1840 and has been retroactively applied to the few who had relevant facts to study. All unrelated speculation was envisioned, even by them, in the only terms people knew--no doubt metaphorically by some although the majority took such speculation literally. There was no data about exoplanets and no imaginable means of acquiring any, so naturally people fit thoughts about them into their existing framework of belief.

Their version of the dream of going to the stars was not totally abandoned; it simply took different forms as the views of the majority changed. When the concept of Heaven as a physical place faded, some people came to believe that worlds of distant stars are the happy abodes of the dead, or more recently, that souls are successively reincarnated on different planets. The latter belief is quite common among adherents of New Age ideas even today.

Though interstellar travel may eventually become possible, no one alive now will ever experience it. Yet the longing is as strong as ever, and many would understand, if not share, what nineteenth-century poet Henry Abbott felt when he wrote, "Seek how we may, / There is no other road across the sky. / And, looking up, I hear star-voices say: / You could not reach us if you did not die."

*

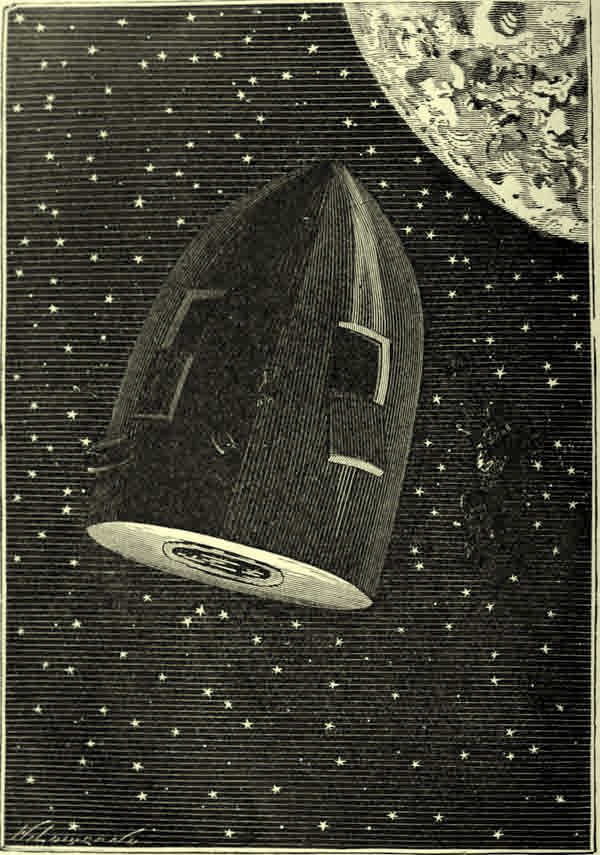

Illustration from an 1874 English translatipn of Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon and a Trip Around it.

The modern version of hope for space travel was born in 1865 with the publication of Jules Verne's novel From the Earth to the Moon, znd a which for the first time suggested that technology might make it possible. "In spite of the opinions of certain narrow-minded people, who would shut up the human race upon this globe, as within some magic circle which it must never outstep," he wrote, "we shall one day travel to the moon, the planets, and the stars, with the same facility, rapidity, and certainty as we now make the voyage from Liverpool to New York." This remark is even more relevant now than when he made it.

Verne may or may not have been serious about interstellar travel, but Winwood Reade was in his 1872 bestseller The Martyrdom of Man, a long, controversial history of humankind that may be the first mention of it in nonfiction. He wrote, "A time will come when science will transform [our bodies] by means which we cannot conjecture... And then, the earth being small, mankind will migrate into space, and will cross the airless Saharas which separate planet from planet, and sun from sun. The earth will become a Holy Land which will be visited by pilgrims from all quarters of the universe." Although the book was widely read, little if any notice was taken of this paragraph. which was no doubt considered too radical to be viewed as a prediction.

During the last few decades of the nineteenth century a number of novels involving space travel appeared. In contrast to past centuries' imaginary flights to idyllic worlds, most featured thrilling adventure, as science fiction has ever since, and the dream of going into space became a focus of the human need for excitement and challenge. Also during this period, hope of actually contacting another world arose, for the sighting of features on Mars thought to be canals convinced the public that there were technologically-advanced Martians and a number of proposals for sending signals to them were made.

In 1898 H. G. Wells' novel The War of the Worlds made the first suggestion of a potential dark side to space travel. No one before him had imagined that inhabitants of other planets might not be friendly. The then-current hope of contacting real Martians precluded any effect the novel might have had on feelings about space. Not until it was dramatized in the form of news in a 1938 radio broadcast was there panic, and that was shirt-lived once the public learned that the news had been fiction The time was not yet ripe for alien invasion drama to reflect underlying emotion. But the idea of hostile visitors had been planted in the collective unconscious, to be enhanced by the countless stories about interstellar war that have appeared since.

The Russian rocket pioneer Konstatin Tsiolkovsky is best known for his technical work, but he also wrote about living in space and believed that humankind will eventually colonize the galaxy.

The Russian rocket pioneer Konstatin Tsiolkovsky wrote extensively about space in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including philosophical works less well-known than his technical ones. He described orbiting habitats in detail and believed that humans will eventually colonize the galaxy. "They will control the climate and the solar system just as they control the Earth," he wrote. "They will travel beyond the limits of our planetary system; they will reach other Suns and use their fresh energy instead of the energy of their dying luminary." But while his work had a strong influence on the Soviet space program, most of his other ideas about humanity conflict with Western views and few of his non-technical writings were translated. Their chief global significance lies in demonstrating that people of all political and religious persuasions share the dream of going to the stars.

During the 1920s and 1930s actual work on rocket technology was carried on by a small number of visionaries, though as recently as 1936 an article in Scientific American declared that it would never be possible to go to the moon because while rockets might power a spaceship there would be no way to navigate (the advent of computers was not foreseen). That didn't slow the growth of public interest in science fiction, which was read by a relatively small number of devotees in the twenties but spread in the thirties and forties to a much wider audience. The comic strips Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon appeared in Sunday newspapers read by millions. Children whose parents had grown up on Westerns were now addicts of their radio and movie serial versions, and in the fifties of the television show Space Cadet. The pulp science fiction scorned in literary circles was supplemented by work of higher quality, some of it in mainstream publications.

Why did this happen at this particular time? It was largely because the technological developments of the early twentieth century--automobiles, electricity in homes, and especially aviation--made people expect more innovations in the future. And to many the future was symbolized by idea of other worlds. The dream of traveling beyond Earth had fascinated people for nearly three hundred years. Now, enhanced by the prospect of rockets, it spread through the collective unconscious of living generations. In 1946 when I was twelve years old, the teacher in a science class read aloud a description of what it would be like to travel in space. I knew at once that this was true and important, though I had never been exposed to any science fiction and was totally ignorant of relevant technology. I told a friend a few days later that I was sure people would get to moon within twenty-five years, an amazingly accurate guess considering that I had no basis for it. I simply sensed that it was time we got to the moon, and evidently many others did, too.

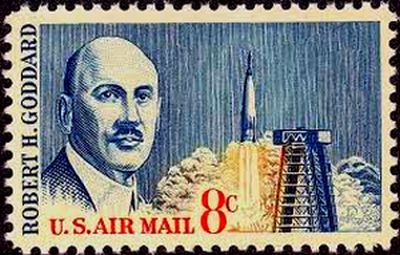

The Ameican rocket scientist Robert Goddard also believed that humanklnd will someday travel o thr sfars, though he kepi his speculaions private so that people would focus on the practical reality of his rocket work.

Not all thoughts about space were positive. The V2 rockets of World War II created an underlying suspicion that danger might someday come from beyond the sky, which was expressed by the alien invasion movies of the 1950s, Unlike more recent ones these movies made no attempt at realism; even to audiences of the time they caused the notion of invaders from space to seem ridiculous, which was the root of their popularity. Though the science of the time rejected the assumption that other planets are inhabited, generations of past belief had established the idea deep in the collective unconscious, and people were no longer so naive as to think that the inhabitants are like angels. Thus this was also the era of the first UFO reports, People who believe in UFOs are not crazy; they simply perceive concepts metaphorically rather than with the logical portion of their minds. Their accounts of what they have seen reveal much about a culture's suppressed thoughts about aliens.

The launch of Sputnik in 1957 changed human outlook on space emotionally as well as in terms of the impact on technology. For the first time, activity beyond this planet was viewed as a part of real life. Initially some people were upset by fear of Soviet superiority, but once it became evident that America could catch up in space they shared the general feeling of excitement. Many aspects of popular culture adopted a space theme, which was often used in advertising because the response was generally positive. Though there were opponents of the space program, their objections were based merely on their belief that the money it cost could be better spent on something else. And so as success followed success, from the first man in orbit to the first spacewalk and on to the effort to actually reach the moon, progress in space became an anchor of optimism in the otherwise troubled and turbulent sixties.

July 20,1869, when the Apollo 11 astronauts landed on the moon, was as Life magazine called it, "the day man left his planetary cradle." An estimated 650 million people worldwide, from Paris and Rome to rural Africa and Lapland, watched on television and cheered.as Neil Armstrong took his first step on the lunar surface and declared, "One giant leap for mankind." Walter Chronkite, the most prominent news anchor of the era, said, "Man's dream and a nation's pledge have now been fulfilled. The lunar age has begun. And with it, mankind's march outward into that endless sky from this small planet circling an insignificant star in a minor solar system on the fringe of a seemingly infinite universe." G. Crowther wrote in the magazine New Scientist that it "can be compared with the original emergence of life from the primordial ocean; it sets a new stage for evolution," a view then shared by many.

And yet the excitement did not last. Despite the continuing enthusiasm of a minority, the public at large turned away from space. Why such a sudden reversal? It is generally said that people had cared only about the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union, and that once it was won they lost interest, This may have been true of some and it was certainly the case with respect to government funding of the space program, but it cannot account for the abrupt loss of feelings that had pervaded Western culture for nearly three hundred years. During most of that time competition in space was unheard of, yet people would have been thrilled to see spaceships explore planets beyond Earth. Those of the past who viewed the sight of them as the hoped-for reward of the heaven-bound after death would have found abandonment of such exploration inconceivable, as would those who were fascinated by the prospect throughout the period when it was seen as a future goal of technology. Nobody ever imagined that humans would reach the moon and then just stop. In the immediate aftermath of Apollo 11 people expected that a trip to Mars would follow before the end of the century. What made so many lose sight of that hope?

In historical accounts of the climactic Apollo 11 moon landing, the importance of the preceding mission Apollo 8, which orbited the moon on Christmas Eve 1968, is often overlooked. Yet actually, it was in several ways more significant. To leave Earth for the very first time and arrive at another world was no small achievement. Apart from the daring it involved, it had a greater impact on human consciousness than is generally recognized. As the astronauts sent their Christmas message, reading from the Book of Genesis while millions watched on television, some people felt as those of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would have, awed by the new world because of their belief that God created it, while others were struck by the continuity of human culture as shown by the use of an ancient text. But underneath, most were shaken by the realization, later enhanced by Apollo 11, that unlike the worlds of their dreams the moon--which traditionally had romantic connotations--is very, very dead. Thus more momentous than the immediate reaction was Apollo 8's transformation of the public's attitude toward our home world.

When people saw this picture of Earth, taken from orbit around the dead moon, they were stunned not only by its beauty but by how small and vulnerable it looked from a distance.

No one had left Earth before. No one had seen it whole, stunningly blue in contrast to the blackness of space. That sight, and the color photo Earthrise taken of it, had an unexpected effect on astronauts and the public alike. They aroused feelings for Earth that hadn't existed when the focus had been on exploring what lay beyond. After the dismaying deadness of the moon, it was suddenly perceived not only as uniquely beautiful but as small and somehow fragile, in need of protection from harm. And so, for good or for ill, the environmental movement was born. `

The good lies in the realization that preservation of Earth's beauty is important and that it does need to be protected from wanton destruction by humans who give no thought to the future. It is less rational to assert that no other spot in the universe is worth anything and to maintain, as many environmentalists do, that humankind can never thrive elsewhere. But it's not a matter of reason, any more than is the reluctance to support space exploration on the part of people who seemingly just don't care. Such reactions are driven by emotions of which these people are often unaware--the same underlying emotions that caused seventeenth-century people to be slow in accepting the new cosmology of their era.

It's not surprising that these emotions have resurfaced. Before Apollo the idea of space travel was abstract--fascinating to think about, but not of real concern to anyone not directly involved. It was thrilling to watch brave men walk on the surface of the moon, and natural to take pride what humans had accomplished. But to be suddenly stricken with awareness that it was all real, that Earth is one very small planet afloat in the vastness of space, vulnerable to whatever perils may appear out of nowhere, was a serious shock. How could people not react with apprehension? How could they not tell themselves that it would be unwise or even unethical to pursue space travel when there are enough problems to deal with at home?

The Irony of it is that the only solution to most of those problems involves going into space and making use of its resources--and that in fact, if an asteroid should approach, without a space-based defense the supposed fragility of Earth would become all too real. But people do not want to know that. When it's explained by space advocates they close their minds. Little more than a year after Apollo 11's success the last three planned moon missions were cancelled for lack of support. Though a limited amount of near-Earth orbital activity was undertaken and robotic landers were sent to Mars, space had ceased be a compelling topic of public interest. An insulating layer of boredom had dampened the enthusiasm people once had for it Eventually a few went so far as to convince themselves that the moon landings didn't really happen.

The desire to see, or at least imagine, worlds unlike our own has not faded, but its focus has changed. Now for entertainment people turn to fantasy, much it based on themes or legends with comforting ties to tradition. Though there is still an audience for science fiction, movies about space, with the exception of Star Trek, have become more and more negative. The ultimate expression of this trend was the conclusion of the 2004-2009 version of Battlestar Galactica, in which the protagonists, after long years in space, destroy their technology by sending their starships into the sun and retreat to a low-tech lifestyle on prehistoric Earth. Nobody on the Internet seemed to view this as a tragedy.

There are still many people who dream of reachng the stars, and entrepreneurs are taking the first steps toward mzking it possible for our descendants to do so.

Yet this does not mean we are confined to our ancestral world forever. Like a child who puts one toe into cold water and pulls back, we sampled the new medium and many shrank from it, But the hesitancy to plunge will not last. Just as to seventeenth-century people a universe full of innumerable uncharted suns did not feel safe, so in our era one in which Earth appears to be the sole haven in a vast expanse of darkness does not. But there are still dreamers--because the population is larger and the need greater, there are more of them than in the past. Activists and entrepreneurs, they are leading the way to a future in which humankind will spread far beyond one small and isolated planet. Fifty-three years passed between the banning of Galileo's book about astronomy and the publication of Fontenelle's hugely popular one. It has now been fifty-four years since the cancellation of the last planned Apollo missions. We are due for a shift in public response.

Sooner or later there will be another new perception of the universe that people shrink from. Strange dimensions? Alien civilizations? Who knows? Yet as always, there will be dreamers to carry humankind forward toward contact with the unknown. The dream of reaching the stars is timeless. However challenging the future may be, that dream will prevail.

Copyright 2024 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.

This essay is included in my book From This Green Earth: Essays on Looking Outward