Why Does the History of Outlook Toward Space Matter?

by Sylvia Engdahl

The following essay consists of the Preface to the 2022 edition of my 1974 nonfiction book The Planet-Girded Suns followed by a revised version of the original Foreword to that book. Few of today's space advocates know or care that widespread belief in inhabited exoplanets has a long history dating back to the late seventeenth century. Here I explain what that fact signifies and why I feel that awareness of it is important.

*

The Planet-Girded Suns is about history, the history of an idea that has been far more prevalent during the past four hundred years than most people realize: the idea that the planets of distant stars are not only habitable, but inhabited. I am not referring to speculation about visitors to our world, either ancient ones or recent UFOs--concepts that arose during the twentieth century which are not accepted by orthodox science. On the contrary, that travel between worlds might ever be possible did not even occur to the scientists, clergymen, and other intellectuals of the late seventeenth through nineteenth centuries who firmly believed that the planets of other suns must have inhabitants. Most argued that God would not have created a world of no use to anyone, but even those who did not put it in religious terms felt that it would be against nature for ours alone to be populated.

Serious opposition to that assumption did not arise until the mid-nineteenth century, and except for a short period in the early twentieth, the belief that there must be many inhabited worlds prevailed. This is not to say, of course, that society at large was aware of the issue or even that stars might be orbited by planets, since most people had too little education to have knowledge of astronomy. But the magazines, newspapers, and poems of the day, directed to the educated minority, made frequent reference to it, as did the writings of such diverse notables as Immanuel Kant, the Puritan minister Cotton Mather, and Benjamin Franklin. It was even included in a few eighteenth-century textbooks for children.

Why should we care today what our forebears believed? Now, what exists on other worlds is a matter for investigation by science. There are countless science books that deal with the issue. This book, originally published in 1974 and updated in 2012 and 2016, contains short sections about the science, but they too are fast falling into the "history" category. Radio astronomers are attempting to detect signals from extraterrestrial civilizations, and more exoplanets are being discovered every day. If you are looking for current scientific information, this is not the place to find it.

Since the late 17th century educated people have longed to know more about the stars.

What you will find is a perspective on the issue that shows public interest in exoplanets and extraterrestrials is no mere passing fad, a subject assumed (erroneously) to have originated in science fiction. It is a fundamental aspect of human thought. It's significant, I think, that people of past centuries were convinced that other inhabited worlds exist, without any scientific evidence whatsoever. This historical fact reveals that human beings have an instinctive sense of kinship with the wider universe and a desire to see the realms that lie beyond this one small planet--and perhaps, eventually, to go there. Our ancestors conceived of such voyages only in a spiritual sense, as occurring after death. But we who have taken our first small steps into space are aware that our descendants may set foot on the worlds of other suns, and those of us who have faith in such a future believe it to be the destiny toward which humankind has been moving throughout history--a step essential to the long-term survival of humankind. Had this been known to the writers of earlier times who spoke of those worlds with longing, they would wonder at the public apathy toward space travel that prevails just when we stand on the threshold of fulfilling their dream.

And yet, today's apparent apathy may be rooted in something much deeper than is commonly supposed. While updating The Planet-Girded Suns for republication, I was struck by a parallel I had not seen before between our time and an earlier era, which puts my worries about our lagging progress in space into a different light. And so in the 2012 of the book I added an Afterword, which has since appeared in The Space Review. It argues that when a new concept of the universe arises, it provokes unconscious anxiety in the public that takes time to fade. Just as in the seventeenth century people were upset by the knowledge that the stars are suns scattered in space rather than lights fixed to a nearby sphere, the growing awareness that Earth is not safely isolated from whatever lies beyond makes many of our contemporaries uneasy. Thus the predominant feelings about spaceships are ambivalent. Nevertheless, if a deep, instinctive desire to see other worlds and a conviction that we're not alone in the universe is indeed common among people of all eras, as our history suggests, we can be sure that those who follow us will not turn back from becoming spacefarers.

*

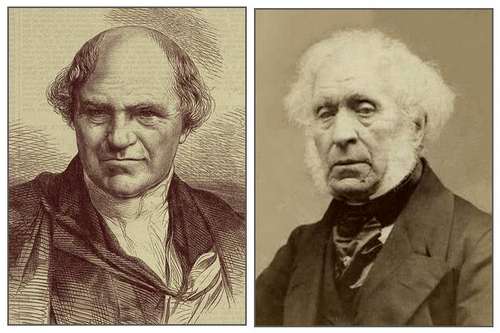

.When Williamn Whewell, an eminent scholar of science, wrote a book auggesting that Earth might be the only inhabited planet in the unverse, he publishred anonymously, but opponents such as Sir David Brewster soon identified him and began a heated debate.

Surprising to most people of today is the fact that belief in inhabited extrasolar worlds is not new. The idea was not, as is commonly believed, invented by science fiction writers. On the contrary, it was accepted by the majority of educated people from the late seventeenth century until the early twentieth century. Scientists, philosophers, clergymen and poets wrote a great deal about it. When in the 1850s the head of a well-known college wrote a book suggesting that there might not be other inhabited worlds, he published it anonymously because he felt it might damage his reputation--and indeed, most of the book's many reviews were disapproving. A prominent university's magazine declared that plurality of worlds was a subject on which "until now it was supposed that there was scarcely room for a second opinion."

This fact does not appear in history books. Until recently the information was to be found mainly in the books and magazines of past centuries. Famous authors of those eras sometimes mentioned their belief in other worlds, but they spoke of it briefly and casually, thinking it too commonplace an idea to merit much discussion. Most of the writers who went intodetail about it are no longer famous. Their books, many of which were bestsellers in their time, have been nearly forgotten. At the time this book was written they existed only in the collections of large libraries, rarely called for, in some cases with bindings so old and brittle that they fell apart in one's hands when one first opened them to read--though by now some have been scanned and are accessible on the Internet.

Such books are not science fiction. Though a few imaginative stories about voyages through space were written as early as the seventeenth century, they were presented as dreams, satire on human society, or fantasy; they did not suggest that space travel would ever become a reality. Not until the late nineteenth century was there any fiction set in the future. The widespread literal belief in extrasolar worlds, on the other hand, was discussed in nonfiction--popular science" works and also religious ones, reflecting their authors' conviction that God would not have created the stars merely for people on this one small planet to look at. All contain speculation about the inhabitants of other planets that was intended to be taken seriously. Readers did not laugh at speculation of that kind, for none of it--even the portions concerning life on the moon--was contrary to the science of its time. Later scientists, who knew more, looked upon it with scorn. Several generations, the generations that came of age during the years between the twentieth century's two world wars, got the impression that science had always laughed at talk of "space people" and that it always would; not until the 1960s did respected authorities begun to speculate again.

Until the middle of the 19th century no one imagined that physical travel between stars might ever become possible. People assumed that the only means of visiting them would be as a spirit, after death.

The speculations in old books, and in most modern scientific ones, have nothing to do with UFOs. The question of whether there are inhabited worlds elsewhere in the universe is separate from the question of whether or not any of those worlds' inhabitants have ever visited our world. Nonfiction of past centuries about extrasolar planets does not mention such a possibility. The idea did not occur to anyone until about the time of World War II. Since then, many people--some of whom are scientists--have investigated records of strange objects seen in the past, and have suggested that these might have involved alien visitors. But science considers the existence of other civilizations far more probable than the notion of their representatives' having come here. And during the former period when almost all educated people were utterly convinced that superior civilizations exist, actual contact between the ones of different solar systems was not even imagined.

Until recently searching for the old writings about extrasolar worlds was a little like a treasure hunt: one could not predict just where they would be found, and one had to look in many places without finding anything. Libraries had reference tools that helped, but these tools were only a beginning; often they provided merely clues leading on to other clues. Occasionally they led to a dead end, such as a work of which the only existing copy was in an inaccessible museum. Yet an astonishing number of relevant volumes were available, even before scholars had published the accounts of past writings that now exist. One could go to a library shelf, take down a magazine well over a hundred years old, and turn to an article that thousands of people must have read when it was new--and that never, perhaps, had been looked on by anyone now alive. The wording of such articles may seem quaint, and their authors may have been ignorant of facts that are now known, but the idea expressed is often closer to what scientists are saying today than to what they said when one's grandparents were young.There are many current science books about extraterrestrial life. This, however, is not a science book. It is the history of an idea. Not all men and women with important ideas are scientists, for science studies only that which can be systematically observed. Long before the invention of the telescope made it possible to observe distant parts of the universe--long before the belief in other worlds became popular--there were men who thought about what might lie beyond Earth. Some had followers, but others were ridiculed or persecuted and at least one was put to death for his theories. Since that time more facts about the universe have been learned; present views of far-off solar systems have scientific foundation. Still, the question of what inhabitants of those solar systems are actually like cannot yet be studied scientifically. When scientists give opinions on it, they are speaking not as authorities but simply as members of the human race, just as their predecessors did. They are expressing not proven truths, but thoughts.

Thoughts about the unknown concern not only science, but religion. For many centuries all speculation about astronomy was inseparable from religion, since the mysteries of the heavens could be explained only in religious terms. Today, when more scientific data can be obtained, there seems to be a firm line between the two. In the past, however, people who drew a line between religion and other affairs placed the subject of other worlds on the "religious" side of that line. Before the twentieth century, few if any separated their personal religious beliefs from their thoughts about what the universe is like. Even those who paid little attention to religion in everyday life considered cosmology--the nature of the cosmos--too unknowable to be viewed as a purely scientific matter.

That astronomical discoveries came into conflict with the religious view current at the time of Copernicus and Galileo is a familiar fact of history. It is often said that learning that the earth moves around the sun lessened people's feeling of central importance. Historians, however, point out that the relation between the earth and the sun was not the real issue. More upsetting was the realization that there are other suns, and therefore, perhaps, other earths--innumerable earths, all of equal importance in the universe. Yet though this was a blow to human pride, before long the public began to look upon the existence of countless worlds as proof of God's power and glory. When no scientific evidence is available, faith of some kind is the only basis for believing in the unseen.

For centuriea people have longed to reach the stars and the worlds surroundng them. as many do today .Thia shows that cotact with the rest of the universe is a basic human wish.

Near the end of the nineteenth century another crisis occurred, one that has not been discussed often. People had been saying for two hundred years that a world would not be created for no purpose, and the only purpose anyone could think of was habitation. Travel from one world to another was not thought possible. So when scientists concluded that the moon and nearby planets are not inhabited, it was natural to start wondering whether theuniverse is really purposeful. The most common argument for extrasolar life seemed less convincing than before. Furthermore, around the turn of the twentieth century a new theory was adopted about the origin of planets. Astronomers began to think that solar systems came into existence accidentally. Such accidents were considered rare; even among people who still viewed cosmology in a religious way, there were many who abandoned their faith in worlds of other suns.

Today, the opposite situation prevails. Since the mid-twentieth century scientists have believed it is highly unlikely that ours is the only inhabited planet in the cosmos, for solar systems have been considered common--a theory recently confirmed by the discovery of many planets orbiting other stars. The likelihood of sentient species elsewhere is accepted by men and women of differing faiths, and also by those with no religious faith. It is frequently assumed by the latter that discovery of extraterrestrial life would be upsetting to religion. This is not true; there has been little if any conflict since the early seventeenth century and most if not all the religious thinkers who have considered the issue believe that existence of other inhabited worlds is compatible with their faith. (Interestingly, a poll has shown that many people think the idea would be disturbing to adherents of other religions, though not to those of their own.) Yet the former Soviet Union's philosophy of dialectical materialism supports the same idea, as did Russian Cosmists before the Soviet era. In 1958 a Soviet astronomer wrote, "The thesis of the existence of life outside the earth is shared in our epoch . . . in equal measure both by the materialists and by the idealists." There are few issues of such importance on which people with conflicting philosophies can so readily agree.

In the early seventies when I wrote The Planet-Girded Suns I was not aware of the Russian Cosmists, about whom little information was then available in English, nor could I locate any information about the views toward extraterrestrial life of religions other than Christianity and Judaism. Since then I have come a across a book dealing with Muslim views based on the Koran. The conviction that our planet is but one of many supporting life appears to be innate in significant numbers of people, regardless of time and place. If this is true, our thoughts about our relation to the universe are not mere idle curiosity, but are basic to our conception of human destiny.

Copyright 1974. 2022 by Sylvia Engdahl

All rights reserved.

This essay is included in my book From This Green Earth: Essays on Looking Outward